Term Ordering Etudes

Term orderings are a key concept in term rewriting and equational reasoning. Equations are my preferred form of mathematics. In particular, well founded term orders, meaning terminating, term orderings are used to prove termination and orient equations into terminating rewrite systems during completion. This orientation enables simplification and subsumption of your equational set, which leads to be efficiency gains over naive equational search.

I’ve found the definitions of term orderings to be so dense as to be inscrutable.

But I’ve soaked on it a while and have some nuggets of understanding.

You can fiddle around with the post here https://colab.research.google.com/github/philzook58/philzook58.github.io/blob/master/pynb/2024-09-23-term_ordering.ipynb

Term Orderings with Variables Have to Be Partial

A lot of the confusion comes from having to deal with variables in your terms.

Variable are really useful though. They achieve pattern matching. Pattern matching is too dang useful to avoid.

For ground terms (no variables), things are more straightforward https://www.philipzucker.com/ground_kbo/ Size of terms more or less works fine.

Similarly strings are more straightforward. Order by size, then tie break lexicographically. This is called shortlex https://www.philipzucker.com/string_knuth/ . Via flattening, ground terms are a subproblem of strings. This is not the case if your term language includes pattern variables.

It is useful to consider a demon trying to subvert your picked order. Variables are intended to stand in for some arbitrary other term. If the demon can pick a term to instantiate your variable that switches your opinion on the ordering, the demon has won.

That is why x = y can never be ordered (at least if you have any opinions about concrete terms). If I say x > y the demon will instantiate y to something awful like f(f(f(f(f(f(f(f(f(a)))))))and x to something nice like a.

Homeomorphic Embedding

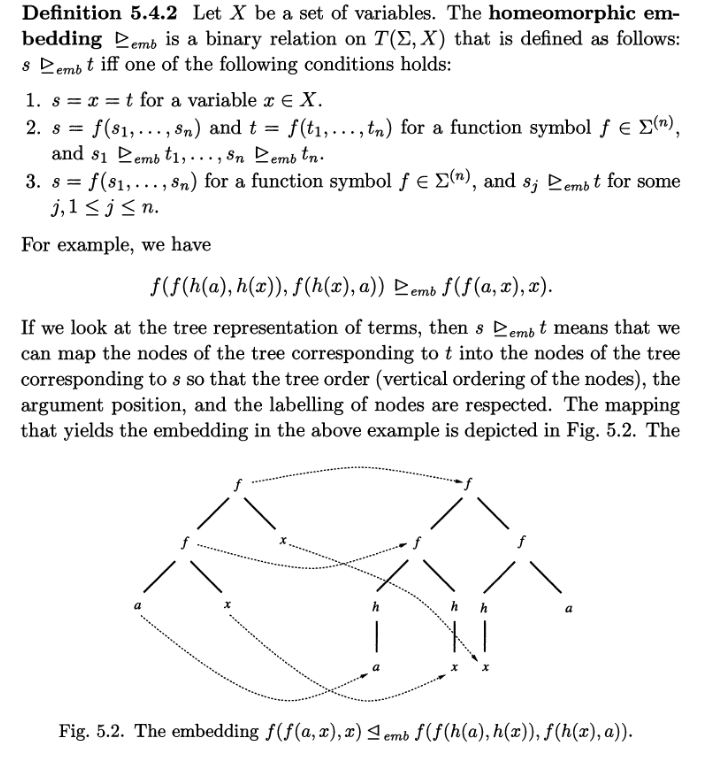

The homeomorphic embedding is the weakest (non strict) simplification ordering where a term is larger than any of it’s subterms (the subterm property). The some degree it is defined as taking the subterm property and then making the order closed under instantiation of variables.

When you shrink a term by fusing out some inner nodes, it gets smaller in some sense. You can’t keep cutting and fusing nodes forever. You’ll eventually be left with a leaf and be stuck.

The relationship between a fused out tree and the original is the homeomorphic embedding.

The definition given in Term Rewriting and All That (TRAAT) can be read as an algorithm for finding an embedding. This algorithm is a straightforward recursive search. Your current pair is either a pair that are identified or a pair for which the one side was fused away and replaced with one of it’s children.

! pip install z3-solver # I'm just using z3 as a handy ast, nothing more.

from z3 import *

# definition traat 5.4.2

def homeo(s,t):

if is_var(s) and s.eq(t):

return True

elif is_app(s) and is_app(t) and s.decl() == t.decl():

return all(homeo(s.arg(i),t.arg(i)) for i in range(s.num_args()))

elif is_app(s) and any(homeo(s.arg(i), t) for i in range(s.num_args())):

return True

else:

return False

v0,v1,v2 = Var(0, IntSort()), Var(1, IntSort()), Var(2, IntSort())

assert homeo(Int('x'), Int('x'))

assert not homeo(Int('x'), Int('y'))

assert homeo(Int('x')+Int('y'), Int('x')+Int('y'))

assert not homeo(Int('x')+Int('y'), Int('y')+Int('x'))

assert homeo(v0,v0)

assert not homeo(v0,v1)

assert homeo(v0 + 1, v0)

assert not homeo(v0, v0 + 1)

Lexicographic Path Ordering

If you asked me to making some ordering for terms, I would say, yeah, just do it lexicographically. In python, if you implement your terms as tuples, this happens automatically

def naive_lex(t,s):

if is_app(t) and is_app(s) and t.decl() == s.decl():

for i in range(t.num_args()):

if naive_lex(t.arg(i), s.arg(i)):

return True

if naive_lex(s.arg(i), t.arg(i)):

return False

return False

else:

dt, ds = t.decl(), s.decl()

return (dt.name(), dt.get_id()) > (s.decl().name(), ds.get_id())

Cody points out this counterexample to the lexicographic ordering. The naive lex ordering says g(p) > g(g(p)).

g = Function('g', IntSort(), IntSort())

p = Int('p')

naive_lex(g(p), g(g(p)))

True

But if we run this system, we obviously have an infinite chain of rewrites.

t = g(p)

for i in range(10):

t = z3.substitute(t, (g(p), g(g(p))))

print(t)

g(g(p))

g(g(g(p)))

g(g(g(g(p))))

g(g(g(g(g(p)))))

g(g(g(g(g(g(p))))))

g(g(g(g(g(g(g(p)))))))

g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(p))))))))

g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(p)))))))))

g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(p))))))))))

g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(g(p)))))))))))

It can be fixed up though. The exact leap of logic here that makes the definition obvious eludes me. You can take pieces of the homeomorphic embedding and mix them in with the pieces of a naive lexicographic ordering.

There is anm intuitive sense in which we want to push bad symbols down and good symbols up. Cody has pointed out an intuition with respect to functional programming definitions. We have an order in which we define our functions in a program. We can recursively call ourselves with complex arguments, but the arguments should involve simpler stuff, and the result of the recursive call should feed into simpler functions. More examples later.

def mem(t,s):

if t.eq(s):

return True

elif is_app(s):

return any(mem(t,si) for si in s.children())

else:

return False

def lpo(s,t):

if s.eq(t): # fast track for equality

return False

elif is_var(t):

return mem(t,s) #lpo1

elif is_var(s):

return False

elif is_app(s):

f, g = s.decl(), t.decl()

if any(si.eq(t) or lpo(si,t) for si in s.children()): #lpo2a

return True

if all(lpo(s,ti) for ti in t.children()): # we lift this out of lop2c and lpp2b

# This subpiece looks similar to naive_lex

if f == g: #lpo2c

for si,ti in zip(s.children(),t.children()):

if si.eq(ti):

continue

elif lpo(si,ti):

return True

else:

return False

raise Exception("Should be unreachable if s == t", s,t)

elif (f.name(), f.get_id()) > (g.name(), g.get_id()): # lpo2b. tie break equal names but idfferent sorts on unique id.

return True

else:

return False

else:

return False

else:

raise Exception("Unexpected case lpo", s,t)

x,y,z,e = Ints('x y z e')

f = Function("f", IntSort(), IntSort(), IntSort())

i = Function("i", IntSort(), IntSort())

log = False

# A bunch of examples from TRAAT

assert not lpo(Int('x'), Int('y'))

assert lpo(Int("y"), Int("x"))

assert not lpo(v0, x)

assert not lpo(x, v0)

assert lpo(x + y, x)

assert lpo(f(v0, e), v0)

assert lpo(i(e), e)

assert lpo(i(f(v0,v1)), f(i(v1),i(v0)))

assert lpo(f(f(v0, v1), v2), f(v0, f(v1, v2)))

# checking anti symmettry

assert not lpo(x, x + y)

assert not lpo(v0, f(v0, e))

assert not lpo(e, i(e))

assert not lpo(f(i(v1),i(v0)), i(f(v0,v1)))

assert not lpo(f(v0, f(v1, v2)), f(f(v0, v1), v2))

assert not lpo(f(v0, f(v1, v2)), f(f(v0, v1), v2))

We can use LPO to determine that the typical recursive definitions of addition and multiplication are terminating.

# prefix with letters to give ordering a_succ < b_plus < c_mul

succ = z3.Function("a_succ", IntSort(), IntSort())

plus = z3.Function("b_plus", IntSort(), IntSort(), IntSort())

mul = z3.Function("c_mul", IntSort(), IntSort(), IntSort())

rules = [

plus(0,v0) == v0,

plus(succ(v0), v1) == succ(plus(v0, v1)),

mul(succ(v0), v1) == plus(mul(v0, v1), v1),

]

def check_lpo_rules(rules):

for rule in rules:

lhs,rhs = rule.arg(0), rule.arg(1)

print(f"{lhs}\t>_lpo\t{rhs} : {lpo(lhs,rhs)}")

check_lpo_rules(rules)

b_plus(0, Var(0)) >_lpo Var(0) : True

b_plus(a_succ(Var(0)), Var(1)) >_lpo a_succ(b_plus(Var(0), Var(1))) : True

c_mul(a_succ(Var(0)), Var(1)) >_lpo b_plus(c_mul(Var(0), Var(1)), Var(1)) : True

Or even that the ackermann function https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ackermann_function is terminating.

ack = z3.Function("d_ack", IntSort(), IntSort(), IntSort())

rules = [

ack(0,v0) == succ(v0),

ack(succ(v0), 0) == ack(v0, 1),

ack(succ(v0), succ(v1)) == ack(v0, ack(succ(v0), v1)),

]

check_lpo_rules(rules)

d_ack(0, Var(0)) >_lpo a_succ(Var(0)) : True

d_ack(a_succ(Var(0)), 0) >_lpo d_ack(Var(0), 1) : True

d_ack(a_succ(Var(0)), a_succ(Var(1))) >_lpo d_ack(Var(0), d_ack(a_succ(Var(0)), Var(1))) : True

Pushing all the associations to the right should obviously terminate. LPO is sufficient to show this. This is despite associativity being a unorientable rule from a naive size perspective.

rules = [plus(plus(v0, v1), v2) == plus(v0, plus(v1, v2))]

check_lpo_rules(rules)

b_plus(b_plus(Var(0), Var(1)), Var(2)) >_lpo b_plus(Var(0), b_plus(Var(1), Var(2))) : True

Distributivity (FOILing out) obviously intuitively has to eventually finish. This is despite it making the term bigger and duplicating v0. It is making progress by pushing mul underneath plus

rules = [mul(v0, plus(v1, v2)) == plus(mul(v0, v1), mul(v0, v2))]

check_lpo_rules(rules)

c_mul(Var(0), b_plus(Var(1), Var(2))) >_lpo b_plus(c_mul(Var(0), Var(1)), c_mul(Var(0), Var(2))) : True

There are also some rewriting algorithms for normalizing boolean expressions. For example disjunctive normal form. Basically we are sorting the order of or, and and not in the terms.

# Define Boolean variables

v0, v1, v2 = Var(0, BoolSort()), Var(1, BoolSort()), Var(2, BoolSort())

neg = Function('c_neg', BoolSort(), BoolSort())

and_op = Function('b_and', BoolSort(), BoolSort(), BoolSort())

or_op = Function('a_or', BoolSort(), BoolSort(), BoolSort())

rules = [

(neg(or_op(v0, v1)) == and_op(neg(v0), neg(v1))),

(neg(and_op(v0, v1)) == or_op(neg(v0), neg(v1))),

(and_op(v0, or_op(v1, v2)) == or_op(and_op(v0, v1), and_op(v0, v2))),

(and_op(or_op(v1, v2), v0) == or_op(and_op(v1, v0), and_op(v2, v0)))

]

check_lpo_rules(rules)

c_neg(a_or(Var(0), Var(1))) >_lpo b_and(c_neg(Var(0)), c_neg(Var(1))) : True

c_neg(b_and(Var(0), Var(1))) >_lpo a_or(c_neg(Var(0)), c_neg(Var(1))) : True

b_and(Var(0), a_or(Var(1), Var(2))) >_lpo a_or(b_and(Var(0), Var(1)), b_and(Var(0), Var(2))) : True

b_and(a_or(Var(1), Var(2)), Var(0)) >_lpo a_or(b_and(Var(1), Var(0)), b_and(Var(2), Var(0))) : True

Bits and Bobbles

Discussions with Cody Roux as always are crucial. Graham, Caleb, Sam and Nate also were a big help.

https://www.cs.tau.ac.il/~nachum/papers/printemp-print.pdf 33 examples of termination

https://homepage.divms.uiowa.edu/~fleck/181content/taste-fixed.pdf a taste of rewriting

f(f(x)) -> g(f(x))

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0304397582900263 orderings for term-reiwritng systems. The OG recursive path ordering paper. It is often th3e case that original work is more readable than later explanations. This may be because the onus of demonstrating the idea is sensible at all is on the original author.

Even though I wrote it, and it is normal python, I find it basically impossible to run lpo in my head.

Why do we want to consider orderings in our automated reasoning / search algorithms?

The intuition there is that we want as much as possible of our reasoning to proceed by evaluation.

Evaluation is the most efficient thing we can do on computers. We get to mutably destroy our terms and know we’ll drive to a normal form. You can write little mini functional programs is essence and hand them off to a knuth bendix or superposition prover. If it picks to term ordering that proves this functional program tetrminating, it in essence will evaluate these terms similarly to how it would evaluate a functional program.

Bake in a simplifier in a principled way

For ordered resolution, the analog is probably that you want as many prolog-like inferences as possible, removing predicates defined by their relation to other predicates.

A different opposite intuition might be that you want to decompile your problem into the highest abstract terms. Usually reasoning at the abstract level can make simple what is very complex at the low level.

This is related to the dogma of the dependent typists that you want equality to be decidable by evaluating terms.

This may also be seen as dignifying macro definitions. Macro expansion for a well stratified (bodies only have previously defined symbols) sequence of macros obviously terminates no matter how explosive the growth of the macros are. So size isn’t really the issue there. But an ordered count of symbols is sufficient in this case. Plus really I think macros terminate by induction on the number of rules you’ve defined. empty rule sets terminates. If you have a rule set that terminates and add a new rule that is only defined in previous symbols, this also terminates.

I find Kruskal’s theorem https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kruskal%27s_tree_theorem quite unilluminating and disturbing. I don’t get it.

You can map your term to a sequence, set, or multiset of paths (paths are sequences / strings of symbols from root to leaf). The sequence of paths is the same thing as naive lex ordering.

Sims mentions that the wreath product ordering on strings is related to recursvie path ordering. Wreath product is take ordering on Xand Y and turn it into (X U Y)*

V = AbAbAbAb…

Frist consider subseqeunce consisting of just elem,ents from X bbbbb and compare. Then lex compare the sequence of the Y sequences (A,A,A,A)

“Let X = {x1,.. . , xJ and assume that X is ordered by -< so that x1 -< x,,. On {xi}there is a unique reduction ordering -<i, namely the will be called the basic ordering by length. The ordering _<1 Z 2 t . . . 2 wreath-product ordering of X determined by -<. This ordering is closely related to the recursive path ordering of Dershowitz. See (Dershowitz 1987)” pg 48 Computation with finitely presented groups

abacccbabaccbaccb

In other words. Order by count of a, then tie break by sequences of counts of b separate by a, then tie break by sequences of a seperated sequences of c separate by b.

# maybe something like this?

def wreath(s,t,n):

if s.count(n) < t.count(n):

s,t = s.split(n), t.split(n)

for si,ti in zip(s,t):

if wreath(s,t,n+1):

return True

else:

return False

("+", ("*", 1, 3), 2) < ("+", ("*", 1, 3), 4)

assert ("b",) > ("a", "b") > ("a", "a", "b") > ("a", "a", "a", "b") > ("a", "a", "a", "a", "b") # ... and so on

What are our examples

Example mul succ plus

functional programs plus(z,X) = X plus(succ(x), y) = succ(plus(x, y)) mul(succ(x), y) = plus(mul(x, y), y)

ackermann ack(0, y) -> succ(y) ack(succ(x), 0) -> ack(x, succ(0)) ack(succ(x), succ(y)) -> ack(x, ack(succ(x), y))

note that x appears twice

macro expansion foo(x,y,z) = bar(x,x,y,z,z,z,z)

association (x + y) + z -> x + (y + z)

distribution x (y + z) -> x y + x * z

negation normal form

Homeomorphic embedding dignifies structural shrinking is well founded.

Subterms are smaller But accoutning for variables.

A term is bigger than another if you can delete nodes to get it.

This is the “closure” of being a subterm in combination with treating variables correctly.

def decls(t):

log = False

def log_arguments(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# Print the function name and arguments

global log

if log:

print(f"Calling {func.__name__} with arguments: {args} and keyword arguments: {kwargs}")

res = func(*args, **kwargs) # Call the original function

if log:

print(f"Calling {func.__name__} with arguments: {args} and keyword arguments: {kwargs} returned {res}")

return res

return wrapper

Calling homeo with arguments: (x, x) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (x, y) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (x + y, x + y) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (x, x) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (y, y) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (x + y, y + x) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (x, y) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (Var(0), Var(0)) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (Var(0), Var(1)) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (Var(0) + 1, Var(0)) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (Var(0), Var(0)) and keyword arguments: {}

Calling homeo with arguments: (Var(0), Var(0) + 1) and keyword arguments: {}

("a",) < ("a", "a")

True

We have an intuition that lexicographic comparison of trees is reasonable.

It isn’t a wll founded order though

0 + (1 + 0) -> (0 + (0 + 1)) ->

lpo. Brute force a simplification order, but once we know that, use naive lex

def lpo

f(f(x)) -> g(f(x))

g(g(x)) -> f(x)

lex combo of orderings works

f(f(x)) -> f(g(f(x))) adjencet fs decrease

from z3 import *

x, y, e = Ints('x y e')

rules = [

(x/x == e),

(x \ x == e),

(x \ y == y),

(y / x * x == y),

(e * x == x),

(x * e == x),

(e / x == x),

(x / e == x),

(x / (y \ x) == y)

]

# Z3 does not handle string rewriting systems directly, but termination can be encoded

s = Solver()

for rule in rules:

s.add(rule)

Cell In[27], line 7

(x \ x == e),

^

SyntaxError: unexpected character after line continuation character

x = Int('x')

rules = [

(1 * x == x),

(x * 1 == x),

(x * x == 1),

(x - x == 1),

((x-) * (x * y) == y)

]

s = Solver()

for rule in rules:

s.add(rule)

Cell In[28], line 7

((x-) * (x * y) == y)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

f = Function('f', IntSort(), IntSort())

g = Function('g', IntSort(), IntSort())

x = Int('x')

rule = f(f(x)) == g(f(x))

rules = [

f(f(x)) == g(f(x)),

g(g(x)) == f(x)

]

rule = f(f(x)) == f(g(f(x)))

D = Function('D', IntSort(), IntSort())

x, y = Ints('x y')

rules = [

(D(x + y) == D(x) + D(y)),

(D(x * y) == (y * D(x)) + (x * D(y))),

(D(x - y) == D(x) - D(y))

]

x, y, z = Ints('x y z')

rule = mul(mul(x, y), z) == mul(x, mul(y, z))

# DNF

neg = Function('neg', IntSort(), IntSort())

and_op = Function('and_op', IntSort(), IntSort(), IntSort())

or_op = Function('or_op', IntSort(), IntSort(), IntSort())

x, y, z = Ints('x y z')

rules = [

(neg(or_op(x, y)) == and_op(neg(x), neg(y))),

(neg(and_op(x, y)) == or_op(neg(x), neg(y))),

(and_op(x, or_op(y, z)) == or_op(and_op(x, y), and_op(x, z))),

(and_op(or_op(y, z), x) == or_op(and_op(x, y), and_op(x, z)))

]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Path_ordering_(term_rewriting)

https://academic.oup.com/comjnl/article/34/1/2/427931 An Introduction to Knuth–Bendix Completion Ajj dick

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10817-006-9031-4 Things to Know when Implementing KBO

https://www.cs.unm.edu/~mccune/mace4/manual/2009-02A/term-order.html

Sims had anb expalantion in terms of wreath product for rpo

https://hol-light.github.io/tutorial.pdf

“The most basic way the LPO orders terms is by use of the weighting function on the top-level function symbols. For example, if we give multiplication a higher weight than addition (by putting it later in the list lis above), this will make the distributive law (x+y)· z = x· z +y · z applicable left-to-right, since it brings a ‘simpler’ operator to the top, even though it actually increases the actual size of the term. In cases where the top operators are the same, the LPO assigns preferences lexicographically left-toright, so that the ordering of the leftmost arguments are considered first, and only in the event of a tie are the others considered one-by-one. This, for example, will tend to drive associative laws like (x + y) + z = x + (y + z) in the left-to-right direction since x is simpler than x + y. We use a generic function lexord to apply a basic ordering ord lexicographically, returning false if the lists are of different lengths:”