Tensors and Graphs: Canonization by Search

There are many interesting syntactic and semantic objects that hold a notion of symmetry that a simple syntax tree can’t quite capture.

- Sets

{1,3,5,2} - Integral expressions $\int dx e^{-x^2}$ have dummy variables

- Sums $\sum_i a_i$ have dummy indices

- lambdas $\lambda x. (x x)$, have bound variables

- resolution clauses $ p(X) \lor q(X,Y)$

- conjunctive database queries $R(a,b) \land R(b,c) \land R(c,a)$,

- Graphs

- indexful tensor expressions $T_{ijk}\epsilon_{ij}$

You sometimes want to manipulate these objects, index them for fast lookup, or check for equality modulo these intrinsic symmetries. I discussed some strategies here https://www.philipzucker.com/hashing-modulo/. In short some possible approaches are

- Canonize to a unique form

- Find a homomorphism into the integers

- Find invariants / fingerprints

For sets for example, canonizing a list representation of a set can be done by simply sorting and deduping it. {1,3,5,2} becomes [1,2,3,5]. Very natural, Eazy peasy.

For lambda terms, a common canonical representation is de bruijn indices $\lambda x. (x x)$ becomes lam(app(var(0),var(0))), which name variables by the number of binders you need to cross to reach their binding lambda.

For binderless alpha invariant things, like a term with unification variables, you can label the variables via a traversal. For example f(X,Y,Y) becomes f(V0, V1, V1) traversing left to right. This particular strategy isn’t stable and therefore is inefficient upon building a new term using this as a subterm, but it is conceptually ok.

But when you start combining set-like things (Associative, commutative and idempotent) with variables, one gets stumped though. This is the case for clauses, tensor expressions, and conjunctive queries. Procedures to name the variables and the procedure to sort the set are entangled. Which do we do first?

One idea is to use a non-ground term ordering to sort the sets. These non-ground term orderings are intrinsically partial though. Also they are way more complicated than anything we’ve discussed so far. They are more for dealing with substitution problems than alpha invariance problems. It is overkill.

You can also replace variables with a marker node V and use that term as a invariant. f(X,Y,Y) becomes f(V,V,V). This is kind of the idea used in discrimination tries. This is an invariant, but it is lossy. It doesn’t distinguish between f(X,Y) and f(X,X).

But how do we actually achieve the canonization approach rather than fingerprinting?

Variables + AC ~ Graph Isomorphism -> Search

I was stumped for while on how to canonize clause-like things, coming up with this and that criteria on naming the variables and breaking ties.

An important revelation is to note that this problem is no going to be solvable in general without search. It is basically a variation of graph canonization, which solves graph isomorphism, something which for which a polynomial time algorithm is unknown. Once we’ve given up on the problem being search free, things become clearer.

Consider canonizing the set of terms {f(X,X), f(X,Y)}.

We can take a step back from particular procedures and note that we are looking through the space of labellings of variables.

{f(v1,v1), f(v1,v0)} or {f(v0,v0), f(v0,v1)} are the options here considering only variable namings. In combination with set permutations this becomes [f(v1,v1), f(v1,v0)] or [f(v0,v0), f(v0,v1)] or [f(v0,v1), f(v0,v0)] or [f(v1,v0), f(v1,v1)].

Our procedures are trying to come up with some method to select one in particular.

A declarative approach is to come up with a criteria for which labelling is best. How do we compare these different possibilities?

Sorting is like saying that we like the lexicographically least among the lists. In our example, that would be [f(v0,v0), f(v0,v1)]. Boom. That’s our canonical form.

So that’s the recipe:

- Describe the space of possible representations

- put some total ordering on it

- the minimum one is the canonical form.

This is a search problem throughout the space of possible representations, which will be typically very large. When we look at a particular problem, we will see many optimizations, propagations, and pruning steps that are possible. Many of the symmetries will factor into smaller subproblems. A well picked total ordering will hopefully have good propagation properties, easy to compute, and be compositional in some sense. We can use noticed invariants to prune the space. For simple problems, these observations will prune the space down into a polynomial time algorithm.

In general though, it won’t. Sometimes we have to canonize by at least some search.

Big Dummy Graph Canonization

Another revelation is that I don’t have to pay attention to the rather group theoretically involved top-of-the-line graph canonization algorithms. I can just do a big dumb search. For small graphs, this works just fine.

There are multiple reasonable variations on the definition of graph. There are also many representations of graphs possible on a computer. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_(abstract_data_type)

For today, let us say that a graph is a set of edges and that edges are a set of two nodes. Here is such a representation of the two edge graph {{3,2}, {0,1}} in python:

{frozenset([3,2]), frozenset([0,1])}

We immediately are tempted to stores undirected edges as sorted tuples because frozenset is so annoying to type.

[(2,3), (0,1)]

And of course, we should sort that list. Looks off as is.

[(0,1), (2,3)]

But actually, unless we seriously have meaningful labels for the nodes, the numbers are meaningless. They are merely a necessary evil bookkeeping device. When I draw a graph on the page, I don’t write the numbers.

I can make some smart constructors that enforce this sorting

def e(i,j):

return (i,j) if i < j else (j,i)

def graph(edges):

# graph should be vertices 0-N

return list(sorted(set(edges))) # dedup and sort

G = graph({e(2,1), e(1,0), e(1,1)})

G

[(0, 1), (1, 1), (1, 2)]

All permutations of vertex labellings should be the same graph. We can define the way a permutation acts on a graph. Permutations are encoded as a list of where each vertex goes under the permutation.

# action of permutation on graph

def act(perm,G):

return graph([e(perm[i],perm[j]) for i,j in G])

assert act([0,1,2], G) == G # identity permutation

assert act([1,0,2], G) == graph([e(2,0), e(0,1), e(0,0)]) # swap 0 and 1. [0 -> 1, 1 -> 0, 2 -> 2]

Finally the brute force canonization routine is remarkably simple. We can use itertools to generate all permutations of the vertices, apply them all, and the take the minimum representation (lexicographically least sorted list of sorted tuples)

import itertools

def canon(G):

N = max(max(e) for e in G) + 1 # number of vertices

return min([act(perm,G) for perm in itertools.permutations(range(N))])

assert canon(G) == canon(act([0,1,2], G))

canon(G)

[(0, 0), (0, 1), (0, 2)]

You can easily improve this brute force routine. Once we’ve selected our node 0, we should select node 1 out of it’s neighbors. We should select something with a self edges first, etc. We should select things with many neighbors to be labelled low, etc.

nauty https://pallini.di.uniroma1.it/ is one system that does efficient graph labelling. It prunes the search space in multiple ways using graph invariants. I’m not exactly sure the ordering it uses on graph labelings, but it does use something.

For more see

- https://cs.stackexchange.com/questions/14354/simple-graph-canonization-algorithm

- https://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~breed/2015COMP362/canonicallabellingpaper.pdf McKay’s Canonical Graph Labeling Algorithm. Very useful down to earth review

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1301.1493 Practical graph isomorphism, II

import pynauty

g = pynauty.Graph(3, directed=False)

g.connect_vertex(0, [1])

g.connect_vertex(1, [2])

print(g)

print(pynauty.autgrp(g)) # (generators, grpsize1, grpsize2, orbits, numorbits)

print(pynauty.certificate(g))

print(pynauty.canon_graph(g))

Graph(number_of_vertices=3, directed=False,

adjacency_dict = {

0: [1],

1: [2],

},

vertex_coloring = [

],

)

([[2, 1, 0]], 2.0, 0, [0, 1, 0], 2)

b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00 \x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00 \x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xc0'

Graph(number_of_vertices=3, directed=False,

adjacency_dict = {

0: [2],

1: [2],

2: [0, 1],

},

vertex_coloring = [

],

)

Big Dumb Tensor Canonicalization

A very similar thing is to canonicalize tensor monomials like $T_{ijk}R_{klmn}S_{ik}$.

This is the same exact problem as canonicalization of resolution clauses or conjunctive queries.

| Tensor | Clause | Conjunctive Query |

|---|---|---|

| $T_{ijk}\epsilon_{ij}$ | $p(X) \lor q(X,Y)$ | $R(a,b) \land R(b,c) \land R(c,a)$ |

| multiply | or | and |

| index | variable | variable |

The more involved tensor canonicalization algorithms https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.08114 also have some forbidding group theory in them. I especially expect tensor expressions to be relatively small, so this seems like overkill.

We can represent a tensor expressions as a list of tuples, where the first field of the tuple is the name of the tensor symbol and the rest are the dummy indices represented by integers.

$T_{ij}R_{jlk}T_{kl}$ becomes [("T", i,k), ("R", j,l,k), ("T", k,l)]).

It looks very similar to the above with a texpr smart constructor removing the AC symmetry of the multiplication, act defining a permutation action on the index names, and then canon canonizing via search. Because we put the tensor names first, it will be in sorted order by tensor name. This means we obviously don’t have to brute search all permutations, but it is a nice one liner to do so. Other orderings may be fruitful for different reasons.

import itertools

i,j,k,l = range(4)

def texpr(ts):

return sorted(ts) # sorting removes AC redundancy of multiplication

t = texpr([("T", i,k), ("R", j,l,k), ("T", k,l)])

def act(perm, T):

return texpr([(head,*[perm[a] for a in args]) for head,*args in T])

assert act([0,1,2,3], t) == t

def canon(T):

N = max(max(args) for head,*args in t) + 1

return min([ act(p,t) for p in itertools.permutations(range(N))])

assert canon(act([0,3,2,1], t)) == canon(t)

canon(t)

[('R', 0, 1, 2), ('T', 2, 1), ('T', 3, 2)]

External unsummed over indices can be dealt with by representing them using some other marker, like a string or something, that is not acted upon by the permutations.

We can embed graph canonization into this problem by making a two index “tensor” called edge. This embedding shows that tensor canonization is no easier than graph canonization and we should expect some search to be required. The tensor expression then becomes the same thing as our graph edge set. You may want to pet in both permutations of the edge tensor. For example,

[("edge", i, j), ("edge", j, i), ("edge", k, l), ("edge", l, k)] is the basically the same as the graph [(i,j), (j,i), (k,l), (l,k)].

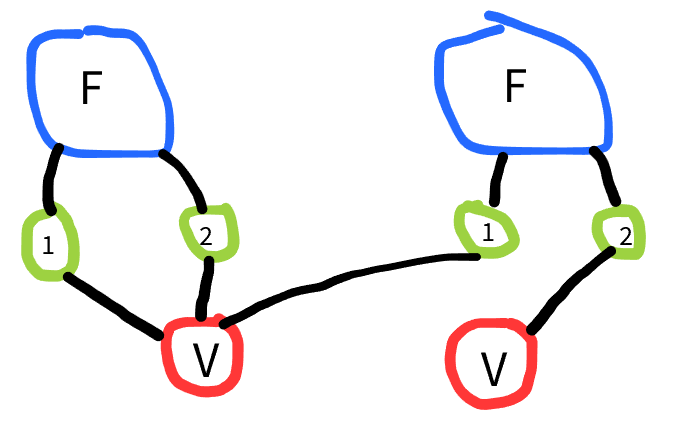

Going the other way, we can embed tensor canonization into labelled/colored graph canonization. F_{i,i}F_{i,j} can be embedded as the vertex labelled graph. This may be useful if we want to use nauty off the shelf for tensor canonization. There are other encodings possible.

We use numbered child vertices to distinguish with port of F things go into. This is because nauty’s definition of graph doesn’t have ports/orderings to the edges attached to a vertex, so we need to break that symmetry. V nodes have no intrinsic name but express equality constraint between variables names as graph connections.

Sometimes these things are encoded as hypergraphs, where variables are represented by hyperedges, which are sets of more than one vertex. more or less that is the same thing.

Bits and Bobbles

A ground knuth bendix baking this stuff in sounds neato. Useful for a glenside variant?

There is a no-go criterion:

If you can embed graph isomorphism/canonization into your problem, you will not find a (generally) search free canonization procedure.

Opposed to this is the go-ahead criterion:

- Graph isomorphism isn’t that bad actually.

- A clever procedure may avoid search in 99% of practical cases.

- Your problem is probably pretty small and not even that unreasonable to brute force.

SAT solver embedding. see below.

Sets (ACI) + lambdas actually isn’t that bad. The binders save you. de bruijn does not care that it has to reach up through the sets to find the binder. From the path perspective, it doesn’t matter. It’s AC + implicit binders which is hard to canonize. It is that https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einstein_notation makes the order of the binder implicit and non existant. But that reflects the interchange law of the implicit summation symbols. CQs and clauses often use unification variables with implicit binders, which have the same issue.

Caleb was the one who first twigged me onto graph canonization frOM his graph hashing work https://arxiv.org/pdf/2002.06653

You can also embed colored graph canonization into uncolored by replacing the colors with edges to unique little graph clusters. That borders of ridiculous though.

Tensor symmettries. Two sided action by groups. permute labels vs permuting the slots.

Slotted egraphs https://michel.steuwer.info/files/publications/2024/EGRAPHS-2024.pdf food for thought. The same sort of permutation thinking is relevant.

Semiring https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.14435 Convergence of Datalog over (Pre-) Semirings

There is not one mathematical definition that deserves ownership to the intuitive pictorial concept of a graph.

Multigraphs, directed graphs, hypergraphs, nodes with labelled ports, single vs multi input/outputs, labelled nodes, labelled edges.

An AST is a single output port, multi-ordered-input port directed graph.

The “thing”, if that is valid concept, is actually the representions modulo these arbitrary choices

Ok, we can label the variables by number of appearances first (an invariant). We can sort by head symbols first maybe. This may not label them all though. Well, we can sort what we’ve got. {f(X,Z), f(Z,Y)}

We can embed this problem into graph isomorphism. That doesn’t guarantee its hard since embedding easy problems into hard ones doesn’t constitute a free lunch.

Even if graph canonization is polynomial time, the algorithm will definitely be complicated. A simple algorithm would have already been found.

When you represent them on paper or in a computer, there are a bunch of arbitrary choices of variables names and orderings. Seemingly, it is difficult to naturally embed them into graphite on 2d paper space or into a linear chunk of memory without making these arbitrary choices.

You can call these arbitrary choices symmetries of the representation. When you put a graph in the computer, you use something to label vertices, like an integer id, even if the object you’re talking about has no intrinsic ids. Any permutation of these node labels still represents the same combinatorial graph in some sense.

When you have a set, you can order in arbitrarily into a list. Permuting the elements of the list represents the same set. Different red-black trees or AVL trees resulting from different input orderings also represent the same set somehow.

When you have variables, you can rename them. $\int f(x) dx = \int f(y) dy$ or $\sum_i a_i = \sum_j a_j$ or $\lambda x. x = \lambda y. y$. This can be modelled as a permutation of names.

Where’s my Computational Group Theory?

I know computational group theory is what the kids crave. It’s a little beside the point. I think it helps prune the search space so it is nice in that regard. If your aim is the automorphism group, rather than canonization persay, then of course ocmputational gorup theory has a bearing

brute force

You can turn a graph of n vertices into a n^2/2 string by listing out all the possible edges This is the same thing as `` representation.

A key point here is that the representation is really useful.

tensor canon

tensor canonization is a topic. I stumbled on it browsing through sympy https://docs.sympy.org/latest/modules/combinatorics/tensor_can.html

https://docs.sympy.org/latest/modules/tensor/tensor.html#sympy.tensor.tensor.TensAdd.canon_bp

from sympy.tensor.tensor import TensorIndexType, tensor_indices, TensorHead, TensorManager, TensorSymmetry

IType = TensorIndexType('IType')

i,j,k,l = tensor_indices('i j k l', IType)

A = TensorHead('A', [IType, IType])

A

G = TensorHead('G', [IType], TensorSymmetry.no_symmetry(1), 'Gcomm')

G(j)

t = A(i,j)*A(-j,k)*A(-k,l)

t2 = A(-k,j)*A(i,k)*A(-j,l)

t.canon_bp() == t2.canon_bp()

A symmettric tensor has a multiset of indices. This is a graph? multigraph? hypergraph?

def act(p, t):

return sorted([(head,*sorted([p[a] for a in args])) for head,*args in t])

foo(g(i), k(j), l(i)) -> (“foo”, (“g”, i), (“k”, j), (“l”, i)). Permutation action + min. Brute force search is silly because we will just get the dpeth first relabelling ordering.

But this is vistiation lex ordering.

What about KBO, LPO etc KBO - they will all be the same size. Unless we weight the indice choice. This could make sense. We want fewer repeated indices. They represent coupling. Order by number of appareances. Tie break by recursion. https://www.philipzucker.com/ground_kbo/ This is not substitution stable. Can be lazy about pushing permutations down once determined.

xACT.

- https://josmar493.dreamhosters.com/ mathemtica analog?

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOaJxzezU8w&list=PLdIcYTEZ4S8TSEk7YmJMvyECtF-KA1SQ2&ab_channel=WolframR%26D web series 20 year of

cadbra

- https://cadabra.science/

- https://docs.sympy.org/latest/modules/combinatorics/tensor_can.html “ The Butler-Portugal algorithm [3] is an efficient algorithm to put tensors in canonical form, solving the above problem.

Portugal observed that a tensor can be represented by a permutation, and that the class of tensors equivalent to it under slot and dummy symmetries is equivalent to the double coset (Note: in this documentation we use the conventions for multiplication of permutations p, q with (p*q)(i) = p[q[i]] which is opposite to the one used in the Permutation class) “

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.08114 Faster Tensor Canonicalization

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S001046550800221X xPerm: fast index canonicalization for tensor computer algebra

- https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_1833414/component/file_2047302/content xTras: A field-theory inspired xAct package for mathematica

- https://europepmc.org/article/pmc/pmc6105178 Computer algebra in gravity research. This paper rules redberry is a tensor CAS?

- https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/OutputFile/1927714 Hiding canonicalisation in tensor computer algebra

- https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/14811/1/thesis.pdf?DDD21+ thesis version

cadabra peeters

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/astronomy-and-space-sciences/articles/10.3389/fspas.2020.00058/full intropductin to numerical relativity

- https://github.com/wojciechczaja/GraviPy Tensor Calculus Package for General Relativity based on SymPy (python library for symbolic mathematics).

sudo apt install cadabra2

young projectors

HJe uses latex $ asa quote for metaprogramming. Interesting.

#https://cadabra.science/static/cadabra_in_ipython.nb.html

from cadabra2 import *

from IPython.display import display, Math, Latex

ex=Ex(r"A_{m n} B^{m n}") # latex expressions

display(Math(str(ex)))

# assign properties to symbols

Symmetric(Ex(r"A_{m n}"))

AntiSymmetric(Ex(r"B_{m n"))

display(Math(str(canonicalise(ex))))

Indices(Ex(r"{m,n,p,q,r,s,t}"))

ex=Ex(r"A_{m n} B^{m p} C_{p q}")

display(Math(str(substitute(ex, Ex(r"A_{m n} -> D_{m q} D^{q}_{n}")))))

display(Math(str(substitute(ex, Ex(r"A_{k n} -> D_{k q} D^{q}_{n}"))))) # so it looks like it is matching modulo names

Automorphism Group

Getting the automorphism group. We can just save the permutations that map the graph representation back into the original graph representation. This is an enumeration of the automorphism group. We probably want to save the group in some kind of factored form though. Also, we can use this info to prune the search space as we go.

G = sorted([(2,1), (1,0)])

import itertools

def perm_graph(perm, G): # a permutation acting on a labelled graph

return tuple(sorted([ tuple(sorted([p[i], p[j]])) for (i,j) in G ]))

print(G)

G = perm_graph(range(3), G)

print(G)

# explicitly list the automorphisms of a graph

def canon(G, N):

autogrp = []

min_graph = G

print(G)

for p in itertools.permutations(range(N)):

G1 = perm_graph(p, G)

print(p,G1)

if G1 == G:

autogrp.append(p)

elif G1 < min_graph:

min_graph = G1

return autogrp, min_graph

canon(G, 3)

# a version where you save the best permutation

def canon(T):

N = max(max(args) in head,*args in t) + 1

return min([ (p, act(p,t)) for p in itertools.permutations(range(N))], key=lambda x: x[1])

Ok, so there is some way of doing that. And maybe this is an example where SAT solvers can really shine. (They have more symmettry breaking in them?)

Clauses as graphs. ordered resolution Queries as graphs Tensor Expressions as graphs

Breaking up the permutations via features

Can we use tree decomposition to make a natural graph canonization that elegant moves on from tree like problems. This is like Caleb’s thing. Dynamic programming approach to canonical ordering.

brute force approach to searching all tree decompositions? Exact solvers must be doing this in some sense.

It’d be nice to not a priori fix the ordering. If some particular graph has a particular unique feature, obviously we want to use that.

{foo(A,B), foo(B,C)} [(“foo”, p[1], p[2]), (“foo”, p[2], p[3])] We could choose “foo” tags to come later but that’d be crazy (?)

Group union find for labelled graphs being interconnected to each other.

Refinement: order coarsely by colors first.

A pile of ground tensor equations would work. G –> (P, canon(G))

This is a canonical form of a labelled graph. It’s a normalizer. Is this the group union find?

TijKij = Rijkk

tensor instruction selection

true global variables are “observed”. They aren’t known distinct though.

seress permutation group algorithms

Sat solving

Matrix binary adjancecy matrix. “Symbolically execute” the comparison routine Branch and bound search for minimum ordering. Permutations can be encoded as a binmary matrix with exactly one true per row and column min_P P^T A P https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permutation_matrix

symettry breaking for SAT uses nauty https://automorphisms.org/ https://arxiv.org/pdf/2406.13557 satsuma Structure-based Symmetry Breaking in SAT

Using Linear programming relaxation of permutation matrix constraint is a classic thing. I wonder how that’d do.

I would be curious to know how kissat compares to nauty presumably it gets smoked nauty is custom tuned.

SAT is useful though. Embedding into nauty’s problem is annoying and confusing.

def lt(G1,G2):

[G1[i,j] and not G2[i,j] for i in len(G1) for j in len(G2)]

# recursive form of lex comparison

# turn if into If. i and j are static.

def lt(G1,G2,i,j):

if i == len(G1) and j == len(G2):

return False

if G1[i,j] and not G2[i,j]:

return True

elif not G1[i,j] and G2[i,j]:

return False

else:

if i+1 == len(G1):

return lt(G1,G2,0,j+1)

else:

return lt(G1,G2,i+1, j)

# or bottom up loop form

def lt(G1,G2):

acc = False

for i in reversed(range(len(G1))):

for j in reversed(len(G1)):

if G1[i][j] == G2[i][j]:

acc = acc

elif G[i,j] and not G2[i,j]:

return

if not G1[i][j] and G2[i][j]:

return True

def lt(perm,G2,N):

acc = BoolVal(False)

for i in reversed(range(N)):

for j in reversed(range(N)):

t = G1

acc = If(

t[i,j] == G2[i,j],

acc,

If(

And(Not(t[i,j]), G2[i,j]),

BoolVal(True),

acc

)

)

if G1(perm(i),perm(j)) == G2(i,j):

acc = acc

elif G[i,j] and not G2[i,j]:

return

if not G1[i][j] and G2[i][j]:

return True

def to_matrix(G):

mat = [[False]*len(G)] * len(G)

for (i,j) in G:

mat[i][j] = True

mat[j][i] = True

return mat

import z3

def compare_graph(G1,G2):

def canon(G):

s = z3.Solver()

Gsym = Function("G", IntSort(), IntSort(), BoolSort())

Function("perm", IntSort(), IntSort())

for i in len(G):

for j in range(i):

s.add(perm(i) != perm(j)) # must be permutation

for i,j in G:

s.add(Gsym(i,j) == True) # "need" to make graph symbolic because perm is symbilic.

perm = Function("perm", IntSort(), IntSort())

def lt(perm,G):

acc = BoolVal(False) # all equal

for i in range(len(G)):

for j in range(i):

acc = If(G[perm[i], perm[j]] < G[i,j], True, acc)

while True:

m = s.model()

s.add(compare_graph(G, m))

if s.check() == unsat:

return G