A Road to Lambda: E-graphs are Ground Completion

E-graphs are a data structure for compactly storing a pile of ground equations. They are the core of a cool methodology for performing equational search for optimized forms of expressions (optimizing tensor computations, floating point expressions, circuits, database queries, etc).

Term rewriting is an old and sophisticated field. See Term Rewriting and All That for a good resource. Learning new stuff every day.

In the most recent variant of e-graph literature I have not seen made explicit some of the connections between the approaches. In this blog post, I try to demonstrate this connection, and insinuate it shows one possible road to extending egraph rewriting to lambda terms and hypothetical reasoning by borrowing from superposition.

Duh?

I think basically the correspondence I’m suggesting is so obvious it’s not even interesting if you’re aware of both worlds or the history of the fields.

But I wasn’t.

And I asked Cody, my resident term rewriting expert (a title he will deny), he wasn’t sure it is right. Also when I ran it past the egraph crew they weren’t so sure either. So maybe there is something here.

Here’s the jist:

- You do completion on a bunch of ground equations like

foo(a) = a, foo(b) = b, b = a. It “solves” them. Completion is guaranteed to terminate on ground equations. - You can also put these equations into an egraph. It also “solves” the problem.

- One can interpret the inner workings of the egraph in completion notions, or you can see egraph techniques as useful optimizations available for ground equations.

- The notion of e-graph canonization is roughly a completion simplification/reduction step on a set of rewrite rules (r-simplify and l-simplify steps).

- The egraph’s union find is in some sense orienting your equations on the fly to an ad hoc term ordering.

- An egraph holds an infinite number of terms in some sense. This same infinite class of terms is inductively defined by running the completed rewrite system backwards.

- The ground rewrite system is in sense inlining away the notion of eclass id. If you make skolem symbols to label enodes, things become more familiar.

- Each eclass is identified with its representative term. Every right hand side in the canonicalized rewrite system is an eclass’ representative term.

Completion

Completion is a semi-decision procedure for converting a set of equations into a terminating confluent rewrite system. Rewrite rules are nice because they are oriented and easy to apply. If completion succeeds (big if), then it produces a decision procedure to determine if two terms are equal. You run the rules in any order you like until you can’t and then check if the remains are equal.

Basic completion is nondestructive/purely accumulating. This makes it simple to think about but leaves a lot of redundancy in space and time.

- pick a term ordering (term orderings are a VERY IMPORTANT CONCEPT. Perhaps the most important concept in term rewriting)

- orient all your equations according to that ordering

- find critical pairs

- reduce them all according to current rewrite rules

- if non trivial pair remains, orient and add to rewrite set

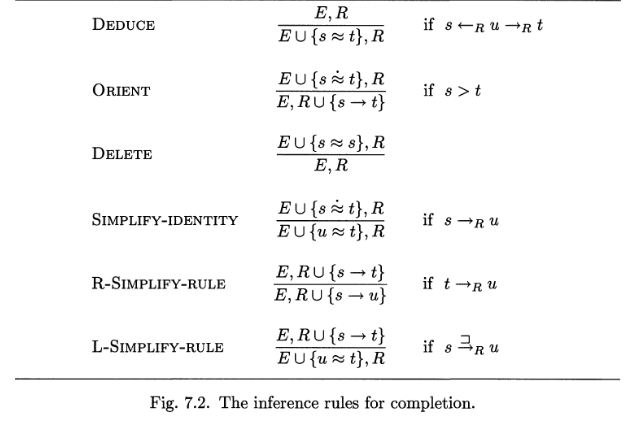

But completion can be presented as a set of inference rules that you may apply however you like.

Basically you take moves from above the line to below the line trying to empty out E and make R confluent. E and R might literally be data structures in your completion program, for example a list of pairs of terms.

See Term Rewriting and All That page 165 for more explanation

See Term Rewriting and All That page 165 for more explanation

Union Find as Atomic Completion

Union finds can be seen as atomic completion (where every term is ground and has 0 arguments).

Union finds are a fast way to store disjoint sets. Basically, you make a tree out of the elements in any set with points pointing up the tree to parents. When you want to merge two set, you set the pointer of one to the other.

There is flexibility when implementing the union operation about who becomes the parent of whom. The textbook use of this redundancy to guarantee the union-find trees stay shallow by tracking extra information. It is not clear if this is performance critical in practice.

But it can also be useful

- Set them according to the order of the arguments. This gives an “

directed union” operation which is not quite clear if it is useful. There is some thought this might be a way to add destructive term rewrites to the typically nondestructive egraph rewriting process. - Use min or max on indices. This makes the system more deterministic. See for example the aegraph which uses this idea to make sure the newest one is the parent.

To think about this as a rewrite system, we associate a symbol with every element and big some arbitrary total order on the symbols. Every time we call union(x,y) we are initiating a system ({x = y}, R). I’ve labelled the operations with the rule tha dignifies them.

class UF():

def __init__(self):

self.rules = {}

def find(self, x):

# `find` reduces x with respect to the current rules (x -R-> retval)

while self.rules.get(x) != None:

x = self.rules.get(x)

return x

def union(self, x, y):

# Do incremental completion starting with

# (E,R) == ({x = y}, self.rules )

x1 = self.find(x) # SIMPLIFY ( {x1 = y} , R)

y1 = self.find(y) # SIMPLIFY ( {x1 = y1}, R)

if x1 == y1: # TRIVIAL ({x1 = x1}, R)

return x1 # (Empty, self.rules)

else:

if x1 < y1: # the "term order"

x1,y1 = y1,x1 # swap

self.rules[x1] = y1 # ORIENT (empty, R U {x1 -> y1})

return y1

def canon(self):

for lhs,rhs in self.rules.items():

self.rules[lhs] = self.find(rhs) # r-simplify

e = UF()

e.union("a", "b")

e.union("c", "d")

e.union("a", "d")

print(e.rules)

e.canon()

print(e.rules)

Because an “atomic” rewriting system is so primitive, there is no need to even consider usage of the l-simplify rule.

Union finds for sets of integers can be implemented using pointers, using array arenas and indices, or using integer to integer maps. For sets of other things that integers, it is easiest to just directly use D->D mappings.Here self.rules is the D->D map/dictionary.

Path compression is a neat trick but not necessary for the union find functioning, and there may be other considerations that override it’s worth. canon can batch up compressing the union find in a single pass. This may be preferred.

Egraph as ground rewrite system

I’ve said before that an egraph is basically a union find smashed together with a hash cons.

I’ve been playing with LogTK which is a library of all sorts of little goodies for building the zipperposition theorem prover.

There’s also a sketch of a python version using some interesting string tricks that I haven’t really thought through below.

- The “egraph” is a rewrite system defined as a map from lhs ground terms to rhs ground terms

findruns the rewrite system to reduce to a canonical formunionreduces it’s two terms and then sets the larger to the smaller in the mapcanonreduces the values in the map and finds nontrivial overlaps in the keys and renormalizes them to a fixed point.

#use "topfind";;

#require "logtk";;

open Logtk

open Containers

(* Ok, a question. Why am I not using this?

https://github.com/sneeuwballen/zipperposition/blob/master/src/core/Congruence.ml

Well, just humor me *)

let ordering = Ordering.kbo (Precedence.default [])

type t = Term.t Term.Map.t

let empty = Term.Map.empty

let rec find (e : t) (x : Term.t) =

let x' = Term.replace_m x e in

if Term.equal x x' then x else find e x'

(* Term.Map.get_or x e ~default:x *)

let union (e : t) (x : Term.t) (y : Term.t) : t =

let x = find e x in

let y = find e y in

let open Comparison in

match Ordering.compare ordering x y with

(* hmm might_flip. Is that a useful fast path? *)

| Eq -> e (* hmm should we perhaps insert self identity stuff in? *)

| Gt -> Term.Map.add x y e

| Lt -> Term.Map.add y x e

| Incomparable ->

(* order should be complete over ground terms. *)

failwith

(Format.sprintf "Unexpected incomparable terms in union: %a %a" Term.pp

x Term.pp y)

let has_subterm_strict (e : t) (t : Term.t) : bool =

Iter.exists

(fun (t, p) -> Term.Map.mem t e && not (Position.equal p Position.Stop))

(Term.all_positions t)

let canonize (e : t) : t =

(* r-simplify *)

(* let e = Term.Map.map (fun t -> find e t) e in *)

let rec canon_step e =

let e' =

Term.Map.fold

(fun lhs rhs e ->

if has_subterm_strict e lhs then

let e = Term.Map.remove lhs e in

(* l-simplify *)

union e lhs rhs

else Term.Map.add lhs (find e rhs) e)

(* r-simplify. Note this is also critica pair finding deduce.

The only critical pairs that can occur are (strict) subterm relationships. *)

e e

in

if Term.Map.equal Term.equal e e' then e else canon_step e'

in

canon_step e

(* Egraphs implicity hold a possibly infinite family of terms *)

let mem (e : t) (t : Term.t) : bool =

let t' = find e t in

(* reduce*)

Iter.exists

(fun t -> Term.subterm ~sub:t' t)

(Iter.append (Term.Map.values e) (Term.Map.keys e))

(*

let foo = let foo = Term.const ~ty:Type.([int] ==> int) (ID.make "foo") in

fun x -> Term.app foo [x]

let a = Term.const ~ty:Type.int (ID.make "a")

let e = union empty a (foo a)

let () = Format.printf "%a" (Term.Map.pp Term.pp) e *)

Start hashconsing those babies and now the Term.t Term.Map.t is basically an Int to Int map being used as a union find

All of this can be cleaned up and done more efficiently, but these are the bones. LogTK includes a number of interesting and useful term indexing mechanisms.

Ok?

Well, what is intriguing is that we have returned to the world of terms. Egraphs are too aggressively optimized, every notion of context is screwed up and trying to get them back is a backwards feeling battle. Really in some respects, even hash conses or any nonlinear usage of terms screw up notions of context.

Lambdas, AC, etc are more straightforward to talk about when you have terms. Completion seems to have a long historied story here. So by pumping the intuition and observations of both sides I think there are interesting things to find.

Superposition is roughly completion under hypothetical contexts. You need to carry along the assumptions you used to get to deriving rewrite rule Equality saturation ought to be implementable as an incomplete strategy of superposition. I do not consider this incompleteness to negate it’s use. Prolog and datalog are incomplete strategies for resolution. They are very operationally useful and map better into inference rules, which is closer to what I care about than first order logic is.

There’s a nice little chart of analogies

| Prop | Eq |

|---|---|

| Resolution | Superposition |

| Prolog | FLP (Curry / Verse) |

| Datalog | Egglog |

Work has been done on integrating lambdas into superposition solvers

The notions of analyses and lattices from egraphs are new I believe from a completion perspective.

Equality saturation is more programmable/operationally understandable in my opinion than superposition. This is analogous to the relationship between resolution and datalog.

That egraphs are used for optimizing terms rather than proving theorems is really really interesting. I think the more easily understood operational nature, plus lower conceptual barrier to entry are important. Using theorem proving technology to find stuff, build compilers, and solve problems beyond theorem proving is a very interesting angle.

The very evocative pictures are also actually crucial for getting users on board.

Egraphs have their own intuition, they can be viewed as foundational and not necessarily subservient to terms.

The egraph world has the notion of e-matching, which I haven’t at all touched in this post. This exact notion of ematching is not so obvious I think from the completion perspective. That a completed rewrite system defines a set of terms that you should search over isn’t so obvious. I don’t know how to map relational ematching back over to completion (yet).

Related Work

- Term rewriting and all that.

- Bohua Zhan - Auto2 AUTO2, a saturation-based heuristic prover for higher-order logic Simon Cruanes pointed this out. Looking at the implementation of the “egraph” https://github.com/bzhan/auto2/blob/master/rewrite.ML gave me a lot of food for thought. I wondered why lambdas were not a problem for him?

- Snyder - fast ground completion

Bits and Bobbles

What is it to be “ground”. Is a lambda term really “ground”?

What I have not touched at all is e-matching or equality saturation. The egraph is more implicit.

The graphical representation of an egraph is canonical, but when you actually have indices the indices aren’t canonical. The reduced ground completion actually is canonical.

It isn’t really lambda terms persay that I care about. beta reduction isn’t the point. Alpha equivalence and proper scoping is more the problem.

It is interesting to note that the words E-matching and E-unification are used in the term rewriting context in a way that precedes their specialization to the egraph.

Given a terminating confluent rewriting system, you can perform these operations via narrowing.

All rewrites by Narrowing.

egraph rewrting could possibly be seen as a particular strategy for completion. The rules also go into R. You can normalize the egraph, then perform steps of l-simplify between the rule-like rewrites and the ground-rewrites. These l-steps are equality stauration steps.

Likewise, datalog is a srategy for resolution. But that does not negate

- AC completion

- Superposition and hypothetical datalog/egglog. resoluton <-> prolog <-> datalog vs superposition <-> functional logic programming <-> egglog

- Lambda

-

Nominal

- incremental addition of these features. Problems with the relational approach. Problems with hash consing.

Tree automata is another observation about how egraphs are related to a previously known strucutre/idea. I have not yet understood why this connection is useful.

Extraction is the biggest concept that does not appear obviously in . Nor analyses, not lattice values. This to some degree can be seen as a specialization of notions of subsumption in superposition.

congruence closure in intensional type theory - We want lambdas for all sorts of reasons. It is hard to know how to push egraph techniques into being more useful without them.

Buchberger and egraphs would be sweet. But do people even do combo buchberger with completion?

Ground Terms

Terms are expressions like sin(cos(x)) or cons(1,cons(2,cons(3,nil))). They are basically the same thing as abstract syntax trees. They are natural thing to be manipulating when you try to figure out how to computerize the sorts of stuff you were taught in algebra. Or they are a perspective on functional programming or compiler stuff.

Terms with variables in them are useful for expressing a couple different notions. You can consider substituting in new terms for the variables. The variables might be used to express patterns, unification, maybe some notions of forall quantification and other such things.

Ground terms are terms without variables in them. Anything you do with terms becomes way simpler if you restrict to ground terms. Ground terms are of course less powerful. Variables play a role similar to universal forall quantification in many situations. You can’t state a large majority of equational axiom or rewrite rules without variables.

Completion

It has not at all been clear to me in the past that completion was interesting. I tend to not care that much about completeness. Why do I want a confluent system? Ok, that’s cool I guess?

So, just guessing, how would one convert equations to good terminating rewrite rules? The obvious thing to do is make left hand sides the bigger looking thing and the right hand side the smaller thing. This is basically the correct intuition.

The notion of “big” and “small” terms is both actually a bit subtle when you try to get precise but also generalizable to the notion of term orders. Term orders are a big non obvious idea in my opinion.

It is very useful to take special cases and consider them

- ground terms vs terms with variables. Variables make things way more complicated.

- Pattern matching vs unification.

The most complicated rule in my opinion is L-simplify. It has this curious side condition about when you are allow to push something from a rewrite rule back into being an equation. You are only allowed to do it if for the two rules in question, only one can rewrite the other.

In the special case of ground terms, the side condition is actually rather simple. You can push a rule back into an equation if one lhs is a subterm of the other rule’s lhs.

In an egraph we incrementally add ground equations. This is like starting with a single equation in E, $({ x = y }, R)$.

Here is a naive python egraph implemented in this style with the usage of the completion axioms annotated. self.rules is $R$

egraph = {}

def term_order(x,y):

lx = len(x)

ly = len(y)

# length and then tie break lexicographically

return lx < ly or (lx == ly and x < y)

class Egraph():

def __init__(self):

self.rules = {}

def find(self, x):

# `find` reduces x with respect to the current rules (x -R-> retval)

done = False

while not done:

done = True

for lhs,rhs in self.rules.items():

y = x.replace(lhs,rhs)

if y != x:

done = False

x = y

return x

def union(self, x, y):

# Do incremental completion starting with

# (E,R) == ({x = y}, self.rules )

x1 = self.find(x) # SIMPLIFY ( {x1 = y} , R)

y1 = self.find(y) # SIMPLIFY ( {x1 = y1}, R)

if x1 == y1: # TRIVIAL ({x1 = x1}, R)

return x1 # (Empty, self.rules)

else:

if term_order(x1, y1): # y1 < x1

x1,y1 = y1,x1 # swap

assert x1 not in self.rules # it should have rewritten if it is

self.rules[x1] = y1 # ORIENT (empty, R U {x1 -> y1})

def canon(self):

done = False

while not done:

done = True

print(self.rules)

for lhs,rhs in self.rules.items():

new_rhs = self.find(rhs)

if rhs != new_rhs:

self.rules[lhs] = new_rhs # r-simplify

done = False

for lhs1,rhs1 in self.rules.items():

for lhs2,rhs2 in self.rules.items():

if lhs1 != lhs2 and lhs1 in lhs2: # l-simplify

done = False

self.rules[lhs2] = lhs2

self.union(lhs2.replace(lhs1, rhs1), rhs2) # ({lhs2[rhs1/lhs1] = rhs2}, R \ {lhs2 -> rhs2})

e = Egraph()

e.union("ffa", "a")

print(e.rules)

e.union("fa", "a")

print(e.rules)

e.canon()

print(e.rules)

Compare with the pseudo code from egg paper.

Union Finds

The egraph is described in various ways, but much emphasis is put on the union-find data structure. This emphasis is somewhat misplaced.

The union find is a data structure for storing disjoint sets. There are two main styles I see, pointer style and array backed union finds. These aren’t really that different. The array backed union find uses array indices essentially as pointers. This is the arena technique for allocation. It’s nice becaue you can swap in a persistent array to get a persistent union find, and you can just copy the array, and because the array probbaly stays less fragmented / has cheaper allocation than calling malloc.

Pointers are defnitely not semantically meaningful and neither are the array indices.

If you are storing actual things in your disjoint sets (like enodes), then you also are maintainig mappings to and from the integer index space. memo

Another style is to inline the union find into just a Map/Dict. Conceptually this is the interface

It is interesting that garbage collectors can traverse the pointer based union find

Indices are not semantically meaningful though. They depend on the order terms went into the egraph. So instead

The union find is an online method of storing the rewrite relation.

String Rewriting and Ground Terms

This is a bit of a side show to the main message of the post, but it is fun. I can build a simple egraph using the regular string matching junk in the python standard lib.

String rewriting is actually quite powerful and can be implemented using the typically available functionality of string.replace.

Strings and ground terms have a lot in common and there is interesting interplay between them.

- We are very used to converting between them via parsing/pretty printing.

- Tries. Discrimination tries can be seen as indexing on a trie of a string like representation. Likewise for Path indexing.

Any string rewriting system can be embedded in a term rewriting system by promoting each character to a unary function symbol. i.e. the string pattern “hello” becomes h(e(l(l(o(X))))) where the pattern variable X binds the suffix of the string.

But conversely a ground patterns and ground terms can be easily converted faithfully to a string rewriting system by merely flattening/serializing/pretty-printing. For example foo(bar,biz(baz)) is literally a string I typed into my blog and is uniquely parseable back into the term. Or it can feel better to convert it to something more spartan like a prefix or postfix looking thing like foo bar biz baz or baz biz bar foo (which is parseable if the arity of the functions is assumed).

Equations or rewrite rules that come from ground terms are very special. Basically, they can’t have partial overlap. The strings “aab” and “baa” have a nontrivial overlap (critical pair) of aabaa. It is impossible to consistently interpret both of these strings are ground terms. Suppose baa means b(a,a). But then aab is something like _(a,a,b(_,_)) It just isn’t a good ground thing anymore. It’s missing bits.

Another thing tempting about all this string talk is whether various string pattern matching and automata techniques become more directly applicable in the egraph.

Any mapping where subterms become substrings works.

Decidability and termination of ground completion

f(a) = a

f(f(f(a))) = a

The consequnces of a ground system are decidable. Egraphs as

Completion is a method you can apply to systems of equations. When applied to ground equations it is guaranteed to terminate successfuly.

Basically, when you find critical pairs between ground terms, you don’t have non trivial overlap. One it a cmplete subterm of the other. So you can’t really generate larger terms compared to the ones you started with. There is a bounded number of terms smaller than the ones you started with or equations containing these terms, hence it completes. Maybe I’m wrong and there is something more subtle at play here, but feels good to me.

This is similar to the datalog termination argument. Datalog rules don’t generate new atoms (in traditional datalog without function symbols or primitive operations on things like arbitrary precision integers). Every relation is bounded above by a full relation of every atom combo. Hence the thing has to stop at some point.

An eager approach to ground completion might just generate every possible term that is smaller than the starting terms.