Modeling Separation Logic with Python Dicts and Z3

Separation logic has made me feel uneasy. I felt a lot better about it once I realized it’s all about partial maps.

Separation logic is a logic (I suppose this is already uneasy point #1) that is useful for reasoning about heaps and memory.

It defines some logical connectives, separating conjunction and wand, that are brothers of the familiar and and implies that somehow intrinsically talk about the heap. Isn’t it weird for the notion of heap to be built into the connectives?

Well, if you already accept temporal logic, which defines logical connectives that talk about time, maybe it isn’t so weird. Also, in general the separating connectives aren’t talking about a heap persay, but some kind of monoid thingo (See O’Hearn review article https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2019/2/234356-separation-logic/fulltext ).

Another perhaps confusing point is: what is the essence of seperation logic? Do you need to already have deeply internalized Hoare logic for reasoning about programs? I think not. The assertion language of separation logic is already interesting. It is a language to describe classes of heaps. Talking about how heaps change throughout a program is a separate complication that I won’t touch today. Somehow I could never get Chris to agree to this point, which puzzles me.

Another thing that confused me is: what is a heap? My first answer is that it is a region of memory, say addresses 0x10000 to 0x20000 at which we are storing data. This is a somewhat machine-centric perspective. Another answer that may be said by someone who thinks about Java and such things is that the heap is an abstract graph of Objects in scope.

But I think an answer that helps when it comes to separation logic is that a heap is a partial map aka a dictionary. We want to think about a mappings when there may be valid and invalid keys / the domain of the map is changing. This is related to the previous two perspectives. While we may preallocate a big hunk of memory for your heap, it is not legal for you to access pieces you have not malloc or to access regions you’ve freed. In this sense, the machine heap’s address space is changing.

So the assertions of separation logic hold in some heap states and not in others.

To make this concrete, there are a couple of interesting programs we can write. The below is in some sense an implementation of the $\models$ relation here http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs.cmu.edu/project/fox-19/member/jcr/www15818As2011/ch2.pdf

Modelling Separation using Python Dicts

Python dictionaries are very convenient partial maps. We can evaluate separation logical assertions on particular heaps to see if they are true or false (whether the dictionary is a model of the statement).

Heap predicates are modelled as python functions Dict -> Bool. For example the empty heap predicate is

def emp(heap):

return len(heap) == 0

emp( {} ) # True

emp( {1 : 2} ) # False

emp( {1 : 2, 3 : 4} ) # False

The assertion that the heap is a singleton is called points to. You see the funny kind of curried shape parametrized predicates need to take here.

def pto(k,v):

def res(heap):

return len(heap) == 1 and k in heap and heap[k] == v

return res

pto(1,3)({}) # False

pto(1,3)({1 : 3}) # True

pto(1,3)( {1 : 3, 4 : 5} ) # False. Perhaps a little surprising. 1 Points to 3 means ONLY 1 -> 3 and nothing extra

The assertion language is modelled as combinators on the predicates. The regular logical connectives just pass the heap along

def ands(p1,p2):

return lambda heap: p1(heap) and p2(heap)

def ors(p1,p2):

return lambda heap: p1(heap) or p2(heap)

def impls(p1,p2):

return lambda heap: not p1(heap) or p2(heap)

ands(emp,emp)({}) # True

ands(pto(1,3) pto(4,5))( {} ) # False for any dictionary

ors(emp, pto(1,3))( {} ) # True

ors(emp, pto(1,3))( {1:3} ) # True

We can actually factor out lifting functions for boolean connectives in general, although we lose short circuiting behavior.

def lift0(b): # lift a boolean

return lambda heap: b

def lift1(boolop): # lift a unary boolean operation

return lambda p: lambda heap: boolop(p(x))

def lift2(boolop2): # lift a binary boolean operation

return lambda p1,p2: lambda heap: boolop2(p1(heap), p2(heap))

nots = lift1(lambda b : not b)

trues = lift0(True)

falses = lift0(False)

Ok, the more interesting one is separating conjunctions *. Separating conjunction is talk about the disjoint merge of two dictionaries. Disjoint merge is defined if the dictionaries do not share any keys. Then it is clearly how to combine the two dictionaries. The new keys are the disjoint union of old keys.

def disjoint_merge(a, b):

assert not any(k in b for k in a)

return {**a, **b}

disjoint_merge({1:4}, {1:2})

Separating conjunction p1 * p2 says that there exists a way to break up the dictionary such that p1 holds of a and p2 holds of b. It is not a priori obvious how to break the dictionary up, so we need to search for a breakup. all_splits is a generator for all ways to break up a list into two lists.

def all_splits(l):

n = len(l)

for i in range(2**n):

left = []

right = []

for b in range(n):

if (i >> b) & 1 == 0:

left.append(l[b])

else:

right.append(l[b])

yield left, right

Using this function we can define sep which is a higher order predicate combinator. Woof.

def sep(p1,p2):

def res(heap):

for (l,r) in all_splits(list(heap.keys())):

if p1( { k : heap[k] for k in l } ) and p2( { k : heap[k] for k in r } ):

return True

return False

return res

sep(pto(1,2), pto(2,3))({ 1:2, 2:3 }) # True

sep(pto(1,2), pto(2,3))({ 1:2, 2:3 , 4:5 }) # False

sep( pto(1,2), pto(1,2) )({ 1 : 2}) # False

Using Z3

We can also model heaps using Z3 Arrays and interpret Separation logic assertions into the first order logical language of Z3. CVC4, a different SMT solver, actually has built in support for separation logic.

To me there are a couple choices

- Model partial map as Array(Key, Option(Value)) using Z3 support for algebraic data types

- Split Partial Map into Array(Key, Value) and

valid : Array(Key,Bool) - Others?

I have a suspicion the latter is preferable. Note that they aren’t quite equivalent, since we need there to exist a default value in the codomain for the second.

I model separation logic assertions as python functions from Array(Key, Value), Array(Key,Bool) -> Z3Bool

The disjointunion relation holds between three valid domain arrays Array(Key, Bool). It states that the disjoint union of a and b is c. It is useful for expressing separating conjunction

from z3 import *

import functools

def disjointunion(a,b,c):

k = FreshConst(a.domain())

return ForAll([k], And( Or(a[k], b[k]) == c[k],

Not(And(a[k],b[k]))

))

# set diff might be an alternative useful formulation

def setdiff(c,a):

return lambda k: And(c[k], Not(a[k])), ForAll([k], Implies(a[k], c[k]))

def pto(k,v):

def res(heap,valid):

k1 = FreshConst(heap.domain())

return And(

ForAll([k1], valid[k1] == (k1 == k)),

heap[k] == v

)

return res

def emp(heap,valid):

k1 = FreshConst(heap.domain())

return ForAll([k1], valid[k1] == False)

def sep(f,g):

def res(heap,valid):

a = FreshConst(valid.sort())

b = FreshConst(valid.sort())

# Should we existentially quantify a and b? We're assuming they'll reach a top level existential

return Exists([a,b], And(disjointunion(a,b,valid), f(heap,a), g(heap,b)))

return res

def lift(x):

def res(heap,valid):

return x

return res

def cell(k, vals):

return functools.reduce(sep, [ pto(k+n, v) for n,v in enumerate(vals)])

# http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs.cmu.edu/project/fox-19/member/jcr/www15818As2011/cs818A3-11.html

# If the heap is extended with a disjoint part in which p1 holds, then p2

# holds for the extended heap.

def wand(p1,p2):

def res(heap,valid):

v2 = FreshConst(valid.sort())

v3 = FreshConst(valid.sort())

# should we skolemize the sitantial into setdiff?

# Or should we define h2 in terms of h3 and h1

# Exists([h3], Implies(p1(setdiff(h3,h)), p2(h3)))

# ForAll([v2], Implies(p1(v2), p2(disjointunionfun()) ))

return ForAll([v2], Exists([v3], Implies( And( p1(heap,v2) , disjointunion(valid,v2,v3)) , p2(heap, v3) )))

return res

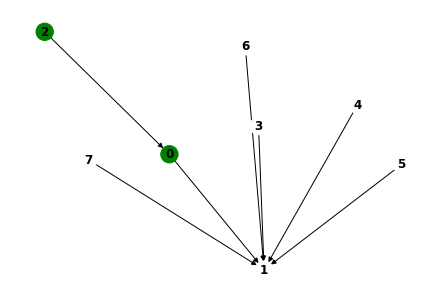

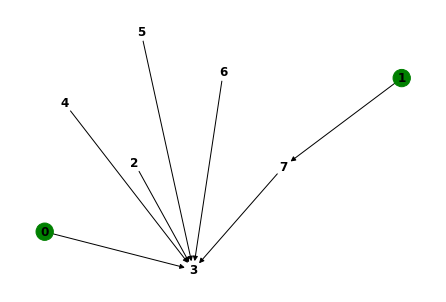

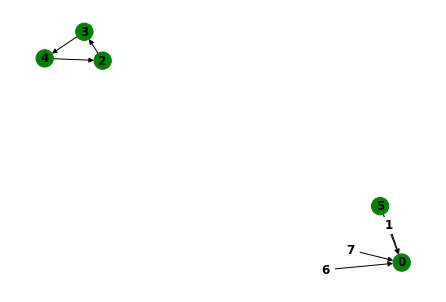

I made a cute little helper function for visualizing the heap models. Using a BitVec(8) domain let’s Z3 actually find models. Using Int domains you will have less / no luck,, since I suspect the quantifiers in the above formulation will kill you for SAT queries. You might be ok for UNSAT queries though.

import networkx as nx

def vis_check(pred, N = 3):

s = Solver()

K = BitVecSort(N)

valid = Array("valid", K, BoolSort())

heap = Array("heap", K, K)

s.add(pred(heap,valid))

if s.check() == sat:

m = s.model()

vals = range(2**N)

try:

edges = [ ( i , m.eval(heap[i]).as_long() ) for i in vals] #if bool(m.eval(valid[i])) ]

colors = ["green" if bool(m.eval(valid[i])) else "white" for i in vals ]

#print(colors)

G = nx.DiGraph()

G.add_nodes_from(vals)

G.add_edges_from(edges)

nx.draw(G, with_labels=True, node_color = colors, font_weight='bold')

except:

pass

return m

else:

print("unsat")

Some examples

vis_check(sep(pto(0,1), pto(0,1))) # UNSAT

vis_check(sep(pto(0,1), pto(2,0)))

m = vis_check( cell(x, [3, 7] ) )

K = BitVecSort(3)

x, y = Consts("x y" ,K)

nil = 0

m = vis_check( sep(pto(nil,nil), sep(cell(x, [3, y] ) , cell(y, [2, nil] ))))

Bits and Bobbles

-

Wand is tougher to do with python dicts. We need to invent all possible extenstions. Hmm.. Wand appears to be very useful for weakest precondition also.

-

Volume 6 of Software Foundations. ICFP paper https://softwarefoundations.cis.upenn.edu/slf-current/index.html

-

The Z3 model is kind of like pretending I’m on a tagged architecture. Isn’t that kind of interesting?

-

Reynolds summer school notes are very nice. http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs.cmu.edu/project/fox-19/member/jcr/www15818As2011/cs818A3-11.html

-

Use garbage collector for dynamic separation logic assertions. The garbage collector has a graph of the current heap. https://docs.python.org/3/library/gc.html

-

Examine what different systems do to examine memory. Frama-C Viper, Dafny, Verifast, Infer

-

Weakest precondition.

-

Hoare logic command is analog of - turnstile. - Is there something physicsy here? Seperation is spacy and temporal is timey. Could you make some kind of relativity thing where predciates about spacelike separated events using seperating conjuction? Relativity style thinking related to comp sci is not new. Lamport diagrams are inspired by slash the same sort of thing as spacetime diagrams and he says this I think.

A curious different approach to the python dictionary thing. I’m not sure it actually works. The idea being that we shouldn’t have to search so much with all_splits. pto Knows exactly what pieces to take out of the heap. So model predicates as Dict -> [Dict] of all possible remainder heaps. If the empty heap is left at the end you have a model?

# a different represdentation. def pred(heap) -> option heap. Doing the set difference

# I guess it is still a search, but we can orient the search a different way. Kind of odd these two perspective are rellated.

def pto(k,v):

def res(heap):

if k in heap and heap[k] == v:

del k in heap # should be doing it pure though

return heap

return None

return res

def emp(heap): # hmnm. This is kind of intruguing. it's the identity function. Am I doing a yoneda? sep and emp form a monoid.

return heap

def sep(p1,p2): # sep is kliesli compose for option

def res(heap):

heap1 = p1(heap)

if heap != None:

return p2(heap)

return None

return res

def ands(p1,p2):

def res(heap):

heap1 = p1(heap)

if heap1 != None:

heap2 = p2(heap)

if heap2 != None:

return heap1 == heap2 # is this right? Kind of in parallel.

return None

return res

def ors(p1, p2): # hmm. Looks like we want it to return [heaps]

def res(heap):

heaps1 = p1(heap)

heaps2 = p2(heap)

return heaps1 + heaps2

# yield from heaps1

return res

- Could perhaps prove general laws about seperating connectives by creating abstract Z3 uninterpeted functions as predicates. A sketch.

# PROVE LAWS

p1 = Function("p1", Array(), Array(), BoolSort())

p2 = Function("p1", Array(), Array(), BoolSort())

heap =

valid =

prove(sep(p1,p2)(heap, valid) == sep(p2,p1)(heap,valid))

def prove_sep( pa, pb ):

heap

valid

prove(Forall([heap,valid], pa(heap,valid) == pb(heap,valid)))