Don't Implement Unification by Recursion

Unification is formal methods speak for solving equations.

The most common form of unification discussed is first order syntactic unification. When it succeeds, it solves a pile of equations no matter what the actual functions represent.

[exists ?X ?Y] foo(bar(?X)) = foo(?Y) has a solution [forall ?Y ?X] ?Y = bar(?X). Or cos(sin(?X)) = cos(?Y) has a solution ?Y = sin(?X). From the perspective of first order unification, it doesn’t matter what cos and sin mean.

Actually implementing unification, similar to most other algorithms that manipulate variables, is kind of the bane of my existence. I avoid it at extreme cost.

It is somewhat surprising that unification is cleaner and easier to implement in an loopy imperative mutational style than in a recursive functional pure style. Typically theorem proving / mathematical algorithms are much cleaner in the second style in my subjective opinion. Unification has too much spooky action at a distance, a threaded state, and can usefully use access to the stack in the form a todo queue to canonize it or reorder it.

A recursion form can be convenient if you need to rebuild a term after you’re done doing whatever you’re doing. In the manual todo list form, you’ll need to store a zipper of some kind to replicate that. Unification typically only returns a substitution and not the original inputs terms specialized to the substitution (although this would be useful for critical pairs, narrowing etc). So for unification, this benefit of recursion is not so useful.

Pattern Matching

Unification can be seen as two sided pattern matching. Pattern matching (like python’s new match-case construct) takes in some tree and allows you to match it against patterns. Patterns maybe contain variables, and when the pattern matches, that branch of the case has the variables bound. Unification allows you to match patterns against patterns.

Pattern matching is much easier to implement. Let’s take a look to make a point about recursive vs iterative implementations.

Like many algorithms, there is a recursive and iterative version. The iterative version more or less reifies the call stack of the recursive version into a normal data structure, keeping around a queue of things to do.

You can also choose whether to manipulate the substitution you’re building purely functionally or mutationally.

# I'm going to work over the z3py ast, because it's useful for knuckledragger and it avoids defining some arbitrary ast.

from z3 import *

def pmatch(pat, t):

subst = {}

def worker(pat, t):

if is_var(pat):

if pat in subst:

return subst[pat].eq(t)

else:

subst[pat] = t

return True

if is_app(pat):

if is_app(t) and pat.decl() == t.decl():

return all(worker(pat.arg(i), t.arg(i)) for i in range(pat.num_args()))

return False

if worker(pat, t):

return subst

# I'm sort of abusing z3's Var here. It's meant for de bruijn vars

x,y,z = Var(0,IntSort()), Var(1,IntSort()), Var(2,IntSort())

assert pmatch(IntVal(3), IntVal(3)) == {}

assert pmatch(IntVal(3), IntVal(4)) == None

assert pmatch(x, IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert pmatch(x + x, IntVal(3) + IntVal(4)) == None

assert pmatch(x + x, IntVal(3) + IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert pmatch(x + y, IntVal(3) + IntVal(4)) == {x : IntVal(3), y : IntVal(4)}

But we can also write this in a loopy todo list form.

from z3 import *

def pmatch_loop(pat, t):

subst = {}

todo = [(pat, t)]

while todo:

pat, t = todo.pop()

if is_var(pat):

if pat in subst:

if not subst[pat].eq(t):

return None

else:

subst[pat] = t

elif is_app(pat):

if not is_app(t) or pat.decl() != t.decl():

return None

todo.extend(zip(pat.children(), t.children()))

return subst

assert pmatch_loop(IntVal(3), IntVal(3)) == {}

assert pmatch_loop(IntVal(3), IntVal(4)) == None

assert pmatch_loop(x, IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert pmatch_loop(x + x, IntVal(3) + IntVal(4)) == None

assert pmatch_loop(x + x, IntVal(3) + IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert pmatch_loop(x + y, IntVal(3) + IntVal(4)) == {x : IntVal(3), y : IntVal(4)}

Inference Rules to the Loop

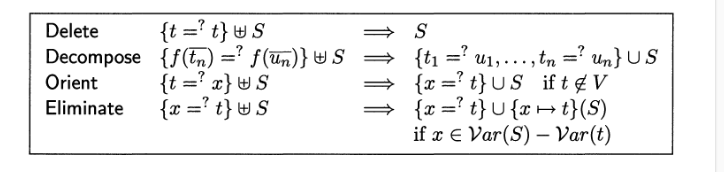

Unification can be presented as an inference system.

Inference rules as compared to pseudocode are nice sometimes. They make things feel mathier. They can make it clear that there is choice available on how to proceed. If you know prolog, rules are cool in that you can write them down as prolog clauses.

The huge downsides of inference rules is that they are a barrier to entry, and the leap from rules to any sort of implementable algorithm can be very non trivial.

If I write unification with a LIFO queue, FIFO queue or some other ordering, it doesn’t matter much. This freedom of ordering is useful in more complex unification domains (E-unification and higher order unification) where you can get locally stumped on how to proceed, so it can be fruitful to pick off of you todo list the easiest to solve equation.

from TRAAT chapter 4

from TRAAT chapter 4

delete remove a trivial equation, decompose matches heads and then zips together their children, orient puts variables in the lhs, eliminate takes an equation in solved for and substitutes the solution everywhere.

A todo queue is basically our multiset S and we choose a particular order to process the equations.

We end up with something like this.

def occurs(x, t):

if is_var(t):

return x.eq(t)

if is_app(t):

return any(occurs(x, t.arg(i)) for i in range(t.num_args()))

return False

def unify(p1,p2):

subst = {}

todo = [(p1,p2)]

while todo:

p1,p2 = todo.pop() # we could pop _any_ of the todos, not just the top.

if p1.eq(p2): # delete

continue

elif is_var(p1): # elim

if occurs(p1, p2):

return None

todo = [(substitute(t1,(p1,p2)), substitute(t2,(p1,p2))) for (t1,t2) in todo]

subst = {k : substitute(v, (p1,p2)) for k,v in subst.items()}

subst[p1] = p2

elif is_var(p2): # orient

todo.append((p2,p1))

elif is_app(p1): # decompose

if not is_app(p2) or p1.decl() != p2.decl():

return None

todo.extend(zip(p1.children(), p2.children()))

else:

raise Exception("unexpected case", p1, p2)

return subst

x,y,z = Var(0,IntSort()), Var(1,IntSort()), Var(2,IntSort())

assert unify(IntVal(3), IntVal(3)) == {}

assert unify(IntVal(3), IntVal(4)) == None

assert unify(x, IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert unify(x, y) == {x : y}

assert unify(x + x, y + y) == {x : y}

assert unify(x + x, y + z) == {x : y, z : y}

assert unify(x + y, y + z) == {x : z, y : z}

assert unify(y + z, x + y) == {y : x, z : x}

# non terminating if no occurs check

assert unify((x + x) + x, x + (x + x)) == None

assert unify(1 + x, x) == None

Eager vs Lazy Substitution

You can wait to remove the solved for variables from your todo expressions. There is a lot of wasteful passes doing nothing in the eager method where I immediately eliminate x everywhere as soon as it is solved.

The lazy method also becomes basically required if you write in a recursive functional style since you do not have access to the todo queue that is on your call stack.

The lazy method is a bit more confusing IMO.

There is also a choice about whether to canonize your substitutions as you use them. The is the analog of path compression in a union find. You can also choose to keep your substitutions in a triangular form where your substitution mapping is never normalized, but then you need to apply it recursively until a fixed point. This style is made popular by minikanren.

def unify_lazy(p1,p2):

subst = {}

todo = [(p1,p2)]

def lookup_var(v):

while v in subst:

v = subst[v]

return v

def lookup_term(t):

if is_var(t):

t = lookup_var(t)

if is_var(t):

return t

if is_app(t):

return t.decl()(*[lookup_term(c) for c in t.children()])

while todo:

p1,p2 = todo.pop()

p1,p2 = lookup_term(p1), lookup_term(p2)

if p1.eq(p2):

continue

elif is_var(p1): # elim

if occurs(p1, p2):

return None

subst[p1] = p2

elif is_var(p2): # orient

todo.append((p2,p1))

elif is_app(p1): # decompose

if not is_app(p2) or p1.decl() != p2.decl():

return None

todo.extend(zip(p1.children(), p2.children()))

else:

raise Exception("unexpected case", p1, p2)

return subst

x,y,z = Var(0,IntSort()), Var(1,IntSort()), Var(2,IntSort())

assert unify_lazy(IntVal(3), IntVal(3)) == {}

assert unify_lazy(IntVal(3), IntVal(4)) == None

assert unify_lazy(x, IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert unify_lazy(x, y) == {x : y}

assert unify_lazy(x + x, y + y) == {x : y}

assert unify_lazy(x + x, y + z) == {x : z, z : y}

assert unify_lazy(x + y, y + z) == {x : z, y : z}

assert unify_lazy(y + z, x + y) == {z : y, y : x}

assert unify_lazy(y + z, x - y) == None

Recursive Form

Finally here is the recursive form. All the looking up and the laziness is what makes it confusing to me. This is basically the lazy iterative form turned back into recursion.

Note that we have kind of removed the ability to inspect which equation in our todo to process next. We are forced to pick some order and then maybe retrieve that ordering by some wacky continuation thing or returning frozen constraints or something.

def unify_rec1(p1,p2, subst):

def lookup_var(v):

while v in subst:

v = subst[v]

return v

def lookup_term(t):

if is_var(t):

t = lookup_var(t)

if is_var(t):

return t

if is_app(t):

return t.decl()(*[lookup_term(c) for c in t.children()])

p1,p2 = lookup_term(p1), lookup_term(p2)

if p1.eq(p2):

return subst

elif is_var(p1): # elim

if occurs(p1, p2):

return None

return {**subst, p1 : p2}

elif is_var(p2): # orient

return unify_rec1(p2,p1, subst)

elif is_app(p1): # decompose

if not is_app(p2) or p1.decl() != p2.decl():

return None

for c in zip(p1.children(), p2.children()):

subst = unify_rec1(c[0], c[1], subst)

if subst is None:

return None

else:

raise Exception("unexpected case", p1, p2)

return subst

def unify_rec(p1,p2):

return unify_rec1(p1,p2,{})

x,y,z = Var(0,IntSort()), Var(1,IntSort()), Var(2,IntSort())

assert unify_rec(IntVal(3), IntVal(3)) == {}

assert unify_rec(IntVal(3), IntVal(4)) == None

assert unify_rec(x, IntVal(3)) == {x : IntVal(3)}

assert unify_rec(x, y) == {x : y}

assert unify_rec(x + x, y + y) == {x : y}

assert unify_rec(x + x, y + z) == {x : y, y : z}

assert unify_rec(x + y, y + z) == {x : y, y : z}

assert unify_rec(y + z, x + y) == {y : x, z : x}

Bits and Bobbles

Thanks to Cody Roux for discussions.

Some unification implementations to compare. I’ve copied some of the relevant bits out far below.

- minikanren , microkanren, faster-minikanren

- harrison https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~jrh13/atp/index.html

- traat https://www21.in.tum.de/~nipkow/TRaAT/ but it also has pascal

- pyres https://github.com/eprover/PyRes/blob/master/unification.py

- prover9 - https://github.com/ai4reason/Prover9/blob/cdca95a51d3c3459b8fd2ebbb5ac1504be2172e3/ladr/unify.c#L345

- unification fd https://hackage.haskell.org/package/unification-fd

- cody’s

- ocaml-alg https://github.com/smimram/ocaml-alg/blob/3905b52a90bc6ac7c91054e1f961b8685b77a30a/src/term.ml#L375

- Graham’s

- eprover https://github.com/eprover/eprover/blob/ab3ea0835b13553d3872b858e93739c2b1aeb0e6/TERMS/cte_match_mgu_1-1.c#L463

- vampire https://github.com/vprover/vampire/blob/6b4efd08c39a0fdc5b28f266dc6b639e807903d7/Kernel/RobSubstitution.cpp#L266

- https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2018/unification/

I don’t know what I’m doing. Do not take this blog post as gospel.

“Don’t implement unification by recursion” is an aggressive way of saying. It’s more “Consider not using recursion”.

Also it’s nice to have the ability to fail the unification by return None instead of raising an error or option monading it. I have come full circle to “write the fucking loop” I guess. All my beloved functional programming has failed me. My cities in tatters. Sigh.

The above loop <-> recursion examples can be systematize as “defunctionalizing the continuation”, one of my favorite functional pearls https://www.cis.upenn.edu/~plclub/blog/2020-05-15-Defunctionalize-the-Continuation/

In one possible low level implementation of unification, the variables are refcells. Unification works via pointer manipulation, pointing the refcell to a piece of a tree or another refcell. It’d be neat and possible for a low level language like rust to support pointer based unification as something akin to a match statement. In logic programming languages, we typically have both unification and backtracking. These aren’t intrinsically coupled features.

Union Find

The pure var to var part of subst is being used as a union find

THis is the find operation

def lookup_var(v):

while v in subst:

v = subst[v]

return v

Union finds can be implemented in different styles. An arena style or a refcell/pointer style.

Occurs Check

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occurs_check

I’m not sure where the idea that the occurs check is the “correct” thing to do and that we only avoid it as a near sighted optimization.

It is an interesting perspective and it is true for things like lists.

There is a related thing to the occurs check, which is correct scoping of forall and exists variables. Curiously, you can make the occurs check deal with this by making all the existential variables in scope parameters to a fresh forall variable in a goal. This is disccussed in the addendum here https://www.philipzucker.com/harrop-checkpoint/ and the Otten provers https://jens-otten.de/tutorial_cade19/ . The occurs check will then detect an ill scoping. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/66068.66075

But for many other function symbols in the theorem proving context, it is perfectly natural to have a loopy equation. pow(?X, 2) = ?X has the solution of 1. It is not an inconsistent thing to ask for. Nor is it an inconsistent universal thing to assert. It is saying multiplication is absorptive, like in boolean algebra.

Also, if we are “scientists” about it, we can take observation it is simpler to just not write the occurs check as evidence that unification is kind of naturally coinductive / loopy / observational / non-well-founded.

Egraph / Flat Style

An interesting style for doing unification is to maintain two mappings.

var -> option obs and a var -> var union find

I discussed this more here. https://www.philipzucker.com/coegraph/

You can process the equations quite lazily. The thing is very uniform. Also you can do bisimulation reduction and “hashcons” equivalent rational terms. The observation table is exactly what you need to do the automata minimization.

Other

Inference Rules

There are a couple different ways to interpret inference rules into code.

We may have one function that has ~one case per inference rule Or we may write a function per inference rule The inference rules may recuyrsively call other inference rules.

We may choose which pieces are inputs and outputs of the rule

- Bottom comes in, top comes out

- top comes in, bottoms come out

- some combo of top and bottom come out

def delete(S):

t,t1 = S.pop()

assert t.eq(t1)

return S

def decompose(S):

t,t1 = S.pop()

assert is_app(t) and is_app(t1) and t.decl() == t1.decl()

S.extend(zip(t.children(), t1.children()))

return S

def orient(S):

t,x = S.pop()

assert is_var(x) and not is_var(t)

S.append((x, t))

def elim(S):

x,t = S.pop()

S = [ ]

return S

# S is a multiset

def permute(S, perm):

return [S[perm[i]] for i in range(len(S))]

other

I am disturbed by the number of times I’ve already written posts about unification, and yet don’t feel that much wiser

I have no memory of this one https://www.philipzucker.com/unification-in-julia/

https://www.philipzucker.com/resolution1/ This was pretty recent. I wrote the same style unification here that I learned from PyRes.

In unification, we talk about “unification variables”. “unification variables” can really refer to things that are very very different.

In theorem proving, there is both forward inference, deriving new theorems from axioms, or backward inference, breaking down goals into easier goals.

Goals and axioms/theorems are very different. Goals are things we want to show are true. Axioms are things we assert true. Unification variables in goals are implicitly existentially quantifier. Unification variables in axioms are implicitly universally quantified.

In prolog, the variables you enter at the prompt are existentially quantified. The variables in the rules and the answers are universally quantified. Running the prolog program converts these existentially quantified questions into universally quantified answers.

variable freshening and context

- Sometimes you want to unify two things where the variables are disjoint even if variable names are shared. This is for example the case when unifying two literals from different clauses, or a prolog goal against a prolog rule head. Just because I wrote

foo(Y,X) :- bar(X).under the query?- foo(X, Y)should not implyX = Y. Implicitly there is a binding at the head of the ruleforall x y, foo(y,x) :- bar(x).. - Sometimes you want to unify two things where the variables can overlap. This is what happens when you apply the factoring rule inside a single clause.

You can freshen all the variables to turn a routine for the second case into the first. Freshening may be a reason to inlcude an integer id in your variable datatype. Still this is pretty clunky and ugly.

Another option is to pass in two extra ctx parameters to unify and every variable is understood with respect to them. Then the second case comes from the first if the two ctx are aliased.

Python is a very imperative language. It doesn’t have good easy access immutable data structures. Basically making a whole new copy of lists or dicts is the only good option. This also informs what is the easiest style to write.

Substitution mapping considered as rewrite rules.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unification_(computer_science)

http://www.cs.man.ac.uk/~hoderk/ubench/unification_full.pdf Comparing Unification Algorithms in First-Order Theorem Proving

https://users.soe.ucsc.edu/~lkuper/papers/walk.pdf Efficient representations for triangular substitutions: A comparison in miniKanren

https://www.proquest.com/openview/f8298f16044b130532ceca70ed4d60c2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y Automated Theorem Proving in Higher-Order Logic - Bhayat thesis

do on z3

https://www.philipzucker.com/resolution1/

E-unificationun https://web.archive.org/web/20200211213303id_/https://publikationen.sulb.uni-saarland.de/bitstream/20.500.11880/25047/1/RR_92_01.pdf

HO-unification as a alngague. When you have full HO unfication, do you need prolog search anymore? You already have so much nontdeterminis

uniification as observation unification as fixed point - When written as an inference system this espcailly makes sense.

Lazy vs eager substitution in unification

Tringular = Lazy

Eager vs lazy normalization of union find.

Recursive vs loop. We have access to the “todo” equations in loop form in the form of some kind of stack.

Inference rule form. I kind of feel like completion you’re moving from E to S, building a valid substitution. E;S. Inference rule form is closer to loop form. You have access to all of E. Typical loop form just pops, but you could use a loop to find the next one to deal with.

Logical Form. Exists([x,y,z], T) == Exist([x,y,z], T) Exists([], T1 = T2) ForAll([], ) # rigid.

occursw check vs scope escape. That prolog trick Just having Exists and ForAll might give you a variation of miller. Ignore lambda?

from dataclass import dataclass

@dataclass

class Var():

x : ExprRef

ctx : Context

def collect_a(self):

res = []

x = self

while x != None:

if isinstance(x, AVar):

res.append(x)

x = x.ctx

return res

class EVar(Var):

x : ExprRef

ctx : Context

class AVar(Var):

def unify(avars, edecls, p1,p2):

edecls = []

def freshe():

edecl = Function("e_", [x.sort() for x in avars])

te = edecl(*avars)

substitute_vars(t, te)

def unify(p1,p2 vctx):

subst = {}

ectx = {}

todo = [([], p1,p2)]

while todo:

ctx,p1,p2 = todo.pop()

if p1.eq(p2):

continue

if is_quantifier(p1):

body, vs = open_binder(p1)

if p1.is_exists():

for v in vs:

ectx[v] = ctx

todo.append((ctx, body, p2))

elif p1.is_forall():

todo.append((ctx + vs, body, p2))

elif p1.is_lambda():

todo.append((ctx + vs, body, p2))

elif is_var(p1):

todo = [(substitute(t1,(p1,p2)), substitute(t2,(p1,p2))) for (t1,t2) in todo]

subst = {k : substitute(v, (p1,p2)) for k,v in subst.items()}

subst[p1] = p2

elif is_var(p2):

todo.append((ctx,p2,p1))

elif is_app(p1):

if not is_app(p2) or p1.decl() != p2.decl():

return None

todo.extend(zip(p1.children(), p2.children()))

else:

raise Exception("unexpected case", p1, p2)

return subst

def unify(p1,p2, vctx):

subst = {}

todo = [(p1,p2)]

while todo:

p1,p2 = todo.pop()

if p1.eq(p2):

continue

elif is_var(p1):

if # do "occurs"

in vctx[p1] # narrow the contx of any var in rhs.

todo = [(substitute(t1,(p1,p2)), substitute(t

def unify_miller(p1,p2, vs):

if p1.decl() in vs: # is_var

#substitute( p1.children(),

# abstract out children

subst[p1.decl()] = Lambda(freshes, substitute(p1, zip(p1.children(), freshes)))

t = Lambda(freshes, substitute(p1, zip(p1.children(), freshes)))

check_no_escape(t)

todo = [ , substitute(p1)]

subst[p1.decl()] = t

todo = []

noescape = []

if is_quantifier(p1)

if is_quantifier(p2) and p1.num_vars() == p2.num_vars() and # sorts:

body, vs = open_binder(p1)

noescape += vs

body2 = instantiate(p2, vs)

todo.append((body,body2))

Exisst x, p(x) = exists y, p(y) # I guess we could allow this? Kind of odd

ex(lam x, p(x))

all(lam x, p(x)) # all is basically treated as a lambda.

{ex x f = ex y g} ==>

{all x, f = all x, g} ==>

{lam x. f = lam x. g} ==>

Z3 Unify

Unification is useful for question asking (exists) and for inferring new facts

questions ~ goals ~ queries ~ BoolRef ~ typed at prolog repl ~ prolog call answers ~ solutions ~ Proof ~ returned to prolog repl ~ prolog return

questions can be forall or exists answers can also be forall or exists

def unify_generalized(t):

"""

Miller nadathur book

alternatig quatifiers then conjuction of equations

Q Q Q Q Q (t1 =t2 /\ t3 = t4 /\ t5 = t6 /\ t7 = t8 /\ t9 = t10)

"""

vars = []

while is_quantifier(t)

vars.append(t.vars)

t = body()

todo = [t]

eqs = []

while todo:

t = todo.pop()

if is_eq(t):

eqs.append(t)

elif is_conj(t):

todo.extend(t.children())

else:

raise ValueError("not a conjunction of equations")

subst = {}

for eq in eqs:

if eq.lhs in subst:

if subst[eq.lhs] != eq.rhs:

raise ValueError("inconsistent equations")

# scope check

else:

subst[eq.lhs] = eq.rhs

def unify_prove(t : z3.BoolRef):

"""

request an exists formula

return a forall _Proof_.

"""

if is_quantifier(t):

assert t.is_exists():

def unify_resolve(q : kd.Proof, t : kd.Proof):

# Take two forall proofs q and t, and return a proof of the resolution of q and t

# forall forall -> forall

def unify_apply(t : BoolRef, t : kd.Proof):

# exist goal + forall proof -> (exist goal', Proof of exists goal' -> exists goal)

# can just use matching?

# forall goal + forall proof -> (forall goal', Proof of forall (goal' -> goal)

from z3 import *

def subterms(t):

ts = set(t)

for c in t.children():

ts |= subterms(c)

return ts

def unify(t1 : ExprRef, t2 : ExprRef, subst, vs):

if t1.eq(t2):

return

if t2 in vs:

t2, t1 = t1, t2

if t1 in vs:

if t1 in subst:

unify(subst[t1], t2, subst, vs)

else:

if t1 in subterms(t2): # occurs

raise Exception("Unification failed")

subst = {i : substitute(k, t1, t2) for i,k in subst.items()} # eager subst. Oh but I can't normalize all my terms too

subst[t1] = t2

else:

if t1.decl() == t2.decl():

for c1,c2 in zip(t1.children(), t2.children()):

unify(c1, c2, subst, vs)

else:

raise Exception("Unification failed")

else:

raise Exception("Unification failed")

unify()

type(Var(0, StringSort()))

x = Int('x')

is_app(x)

True

from z3 import *

def z3_match(t : ExprRef, pat : ExprRef) -> dict[z3.ExprRef, z3.ExprRef]:

"""

Pattern match t against pat. Variables are constructed as `z3.Var(i, sort)`.

Returns substitution dict if match succeeds.

Returns None if match fails.

Outer quantifier (Exists, ForAll, Lambda) in pat is ignored.

"""

if z3.is_quantifier(pat):

pat = pat.body()

subst = {}

todo = [(t,pat)]

while len(todo) > 0:

t,pat = todo.pop()

if t.eq(pat):

continue

if z3.is_var(pat):

if pat in subst:

if not subst[pat].eq(t):

return None

else:

subst[pat] = t

elif z3.is_app(t) and z3.is_app(pat):

if pat.decl() == t.decl():

todo.extend(zip(t.children(), pat.children()))

else:

return None

else:

raise Exception("Unexpected subterm or subpattern", t, pat)

return subst

# not worth doing

def match_quant(t,p):

if is_quantifier(p):

return z3_match(t,p.body())

else:

raise Exception("Not a quantifier")

R = RealSort()

x,y,z = Reals('x y z')

z3_match(x, Var(0, R))

pmatch(x + y, Var(0, R) + Var(1, R))

pmatch(x + y, Var(0, R) + Var(1, R) + Var(2, R))

pmatch(x + y + x, Var(0, R) + Var(1, R) + Var(0, R))

pmatch(x + y + x*6, Var(0, R) + Var(1, R) + Var(2, R))

match_quant(x + y + x*6 == 0, ForAll([x,y,z], x + y + z == 0))

# If I wanted deeper matching into binders, then what?

{Var(0): x*6, Var(1): y, Var(2): x}

E-unify Egraph

# E-unification Egraph Style

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Any

@dataclass

class Unify():

uf: list[int]

obs: dict[int, tuple[Any, tuple[int]]]

def __init__(self):

self.uf = []

self.obs = {}

def make_var(self):

v = len(self.uf)

self.uf.append(v)

return v

def add_term(self, t):

# try to check for rationality?

if isinstance(t, int):

return t

head, *args = t

args = tuple(self.add_term(arg) for arg in args)

# we're not interning at all here, which is fine but inefficient.

x = self.make_var()

self.observe(x, (head, args))

return x

def find(self, x):

while self.uf[x] != x:

x = self.uf[x]

return x

def union(self, x, y):

x = self.find(x)

y = self.find(y)

self.uf[x] = y

return y

def merge_obs(self, obs, obs1): # unify_flat

head, args = obs

head1, args1 = obs1

if head != head1:

raise Exception("head mismatch")

if len(args) != len(args1):

raise Exception("arity mismatch")

for a,a1 in zip(args, args1):

self.union(a,a1)

def observe(self, x, obs):

x = self.find(x)

o = self.obs.get(x)

if o != None:

self.merge_obs(o, obs)

self.obs[x] = obs

def extract(self,x):

# assuming a well founded term. Could extract the rational term?

x = self.find(x)

f = self.obs.get(x)

if f == None:

return x

else:

head, args = f

return (head, *[self.extract(a) for a in args])

def rebuild(self):

while True:

newobs = {}

# "unobserved" vars aren't be merged. unobserved is actually Maximally observed, i.e. has identity.

for x,obs in self.obs.items():

x1 = self.find(x)

obs1 = self.obs.get(x1)

if obs1 != None:

self.merge_obs(obs, obs1)

(head, args) = obs

newobs[x1] = (head, tuple(map(self.find, args)))

if self.obs == newobs:

break

self.obs = newobs

U = Unify()

x = U.make_var()

y = U.make_var()

z = U.make_var()

print(U)

#U.union(x,y)

a_x = U.add_term(("a", ("b", z)))

b_y = U.add_term(("a", y))

U.union(a_x, b_y)

print(U)

U.rebuild()

print(U)

U.extract(a_x)

Example Unification algorithms

PyRes

# https://github.com/eprover/PyRes/blob/master/unification.py

def occursCheck(x, t):

"""

Perform an occurs-check, i.e. determine if the variable x occurs in

the term t. If that is the case (and t != x), the two can never be

unified.

"""

if termIsCompound(t):

for i in t[1:]:

if occursCheck(x, i):

return True

return False

else:

return x == t

def mguTermList(l1, l2, subst):

"""

Unify all terms in l1 with the corresponding terms in l2 with a

common substitution variable "subst". We don't use explicit

equations or pairs of terms here - if l1 is [s1, s2, s3] and l2 is

[t1, t2, t3], this represents the set of equations {s1=t1, s2=t2,

s3=t3}. This makes several operations easier to implement.

"""

assert len(l1)==len(l2)

while(len(l1)!=0):

# Pop the first term pair to unify off the lists (pop removes

# and returns the denoted elements)

t1 = l1.pop(0)

t2 = l2.pop(0)

if termIsVar(t1):

if t1==t2:

# This implements the "Solved" rule.

# We could always test this upfront, but that would

# require an expensive check every time.

# We descend recursively anyway, so we only check this on

# the terminal case.

continue

if occursCheck(t1, t2):

return None

# Here is the core of the "Bind" rule

# We now create a new substitution that binds t2 to t1, and

# apply it to the remaining unification problem. We know

# that every variable will only ever be bound once, because

# we eliminate all occurances of it in this step - remember

# that by the failed occurs-check, t2 cannot contain t1.

new_binding = Substitution([(t1, t2)])

l1 = [new_binding(t) for t in l1]

l2 = [new_binding(t) for t in l2]

subst.composeBinding((t1, t2))

elif termIsVar(t2):

# Symmetric case

# We know that t1!=t2, so we can drop this check

if occursCheck(t2, t1):

return None

new_binding = Substitution([(t2, t1)])

l1 = [new_binding(t) for t in l1]

l2 = [new_binding(t) for t in l2]

subst.composeBinding((t2, t1))

else:

assert termIsCompound(t1) and termIsCompound(t2)

# Try to apply "Decompose"

# For f(s1, ..., sn) = g(t1, ..., tn), first f and g have to

# be equal...

if terms.termFunc(t1) != terms.termFunc(t2):

# Nope, "Structural fail":

return None

# But if the symbols are equal, here is the decomposition:

# We need to ensure that for all i si=ti get

# added to the list of equations to be solved.

l1.extend(termArgs(t1))

l2.extend(termArgs(t2))

return subst

def mgu(t1, t2):

"""

Try to unify t1 and t2, return substitution on success, or None on failure.

"""

res = mguTermList([t1], [t2], Substitution())

res2 = "False"

if res:

res2 = "True"

# print("% :", term2String(t1), " : ", term2String(t2), " => ", res2);

return res

Minikanren

%file /tmp/minikanren_unif.scm

;; http://webyrd.net/scheme-2013/papers/HemannMuKanren2013.pdf

;; https://github.com/jasonhemann/microKanren/blob/master/microKanren.scm

; Jason Hemann and Dan Friedman

;; microKanren, final implementation from paper

(define (var c) (vector c))

(define (var? x) (vector? x))

(define (var=? x1 x2) (= (vector-ref x1 0) (vector-ref x2 0)))

(define (walk u s)

(let ((pr (and (var? u) (assp (lambda (v) (var=? u v)) s))))

(if pr (walk (cdr pr) s) u)))

(define (ext-s x v s) `((,x . ,v) . ,s))

(define (== u v)

(lambda (s/c)

(let ((s (unify u v (car s/c))))

(if s (unit `(,s . ,(cdr s/c))) mzero))))

(define (unit s/c) (cons s/c mzero))

(define mzero '())

(define (unify u v s)

(let ((u (walk u s)) (v (walk v s)))

(cond

((and (var? u) (var? v) (var=? u v)) s)

((var? u) (ext-s u v s))

((var? v) (ext-s v u s))

((and (pair? u) (pair? v))

(let ((s (unify (car u) (car v) s)))

(and s (unify (cdr u) (cdr v) s))))

(else (and (eqv? u v) s)))))

Harrison

%%file /tmp/harrison.ml

(* ========================================================================= *)

(* Unification for first order terms. *)

(* https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~jrh13/atp/OCaml/unif.ml *)

(* Copyright (c) 2003-2007, John Harrison. (See "LICENSE.txt" for details.) *)

(* ========================================================================= *)

let rec istriv env x t =

match t with

Var y -> y = x or defined env y & istriv env x (apply env y)

| Fn(f,args) -> exists (istriv env x) args & failwith "cyclic";;

(* ------------------------------------------------------------------------- *)

(* Main unification procedure *)

(* ------------------------------------------------------------------------- *)

let rec unify env eqs =

match eqs with

[] -> env

| (Fn(f,fargs),Fn(g,gargs))::oth ->

if f = g & length fargs = length gargs

then unify env (zip fargs gargs @ oth)

else failwith "impossible unification"

| (Var x,t)::oth | (t,Var x)::oth ->

if defined env x then unify env ((apply env x,t)::oth)

else unify (if istriv env x t then env else (x|->t) env) oth;;

(* ------------------------------------------------------------------------- *)

(* Solve to obtain a single instantiation. *)

(* ------------------------------------------------------------------------- *)

let rec solve env =

let env' = mapf (tsubst env) env in

if env' = env then env else solve env';;

(* ------------------------------------------------------------------------- *)

(* Unification reaching a final solved form (often this isn't needed). *)

(* ------------------------------------------------------------------------- *)

let fullunify eqs = solve (unify undefined eqs);;

Prover9

%%file /tmp/prover9.c

BOOL unify(Term t1, Context c1,

Term t2, Context c2, Trail *trp)

{

Trail tpos, tp, t3;

int vn1, vn2;

DEREFERENCE(t1, c1) /* dereference macro */

DEREFERENCE(t2, c2) /* dereference macro */

/* Now, neither t1 nor t2 is a bound variable. */

if (VARIABLE(t1)) {

vn1 = VARNUM(t1);

if (VARIABLE(t2)) {

/* both t1 and t2 are variables */

if (vn1 == VARNUM(t2) && c1 == c2)

return TRUE; /* identical */

else {

BIND_TR(vn1, c1, t2, c2, trp)

return TRUE;

}

}

else {

/* t1 variable, t2 not variable */

if (occur_check(vn1, c1, t2, c2)) {

BIND_TR(vn1, c1, t2, c2, trp)

return TRUE;

}

else

return FALSE; /* failed occur_check */

}

}

else if (VARIABLE(t2)) {

/* t2 variable, t1 not variable */

vn2 = VARNUM(t2);

if (occur_check(vn2, c2, t1, c1)) {

BIND_TR(vn2, c2, t1, c1, trp)

return TRUE;

}

else

return FALSE; /* failed occur_check */

}

else if (SYMNUM(t1) != SYMNUM(t2))

return FALSE; /* fail because of symbol clash */

else if (ARITY(t1) == 0)

return TRUE;

else { /* both complex with same symbol */

int i, arity;

tpos = *trp; /* save trail position in case of failure */

i = 0; arity = ARITY(t1);

while (i < arity && unify(ARG(t1,i), c1, ARG(t2,i), c2, trp))

i++;

if (i == arity)

return TRUE;

else { /* restore trail and fail */

tp = *trp;

while (tp != tpos) {

tp->context->terms[tp->varnum] = NULL;

tp->context->contexts[tp->varnum] = NULL;

t3 = tp;

tp = tp->next;

free_trail(t3);

}

*trp = tpos;

return FALSE;

}

}

} /* unify */

Ocaml alg

%%file /tmp/ocaml_alg.ml

(* https://github.com/smimram/ocaml-alg/blob/main/src/term.ml#L375 *)

(** Most general unifier. *)

let unify t1 t2 =

(* Printf.printf "UNIFY %s WITH %s\n%!" (to_string t1) (to_string t2); *)

let rec aux q s =

match q with

| [] -> s

| p::q ->

match p with

| Var x, t ->

if occurs x t then raise Not_unifiable;

let s' = Subst.simple x t in

let f = Subst.app s' in

let q = List.map (fun (t1,t2) -> f t1, f t2) q in

let s = Subst.compose s s' in

aux q (Subst.add s x t)

| t, Var x -> aux ((Var x,t)::q) s

| App (f1,a1), App (f2,a2) ->

if not (Op.eq f1 f2) then raise Not_unifiable;

let q = (List.map2 pair a1 a2) @ q in

aux q s

in

let s = aux [t1,t2] Subst.empty in

assert (eq (Subst.app s t1) (Subst.app s t2));

s

TRAAT

%%file /tmp/traat.ml

(*** https://www21.in.tum.de/~nipkow/TRaAT/programs/trs.ML The basics of term rewriting: terms, unification, matching, normalization

ML Programs from Chapter 4 of

Term Rewriting and All That

by Franz Baader and Tobias Nipkow,

(Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Copyright (C) 1998 by Cambridge University Press.

Permission to use without fee is granted provided that this copyright

notice is included in any copy.

***)

type vname = string * int;

datatype term = V of vname | T of string * term list;

(* indom: vname -> subst -> bool *)

fun indom x s = exists (fn (y,_) => x = y) s;

(* app: subst -> vname -> term *)

fun app ((y,t)::s) x = if x=y then t else app s x;

(* lift: subst -> term -> term *)

fun lift s (V x) = if indom x s then app s x else V x

| lift s (T(f,ts)) = T(f, map (lift s) ts);

(* occurs: vname -> term -> bool *)

fun occurs x (V y) = x=y

| occurs x (T(_,ts)) = exists (occurs x) ts;

exception UNIFY;

(* solve: (term * term)list * subst -> subst *)

fun solve([], s) = s

| solve((V x, t) :: S, s) =

if V x = t then solve(S,s) else elim(x,t,S,s)

| solve((t, V x) :: S, s) = elim(x,t,S,s)

| solve((T(f,ts),T(g,us)) :: S, s) =

if f = g then solve(zip(ts,us) @ S, s) else raise UNIFY

(* elim: vname * term * (term * term) list * subst -> subst *)

and elim(x,t,S,s) =

if occurs x t then raise UNIFY

else let val xt = lift [(x,t)]

in solve(map (fn (t1,t2) => (xt t1, xt t2)) S,

(x,t) :: (map (fn (y,u) => (y, xt u)) s))

end;

(* unify: term * term -> subst *)

fun unify(t1,t2) = solve([(t1,t2)], []);

(* matchs: (term * term) list * subst -> subst *)

fun matchs([], s) = s

| matchs((V x, t) :: S, s) =

if indom x s then if app s x = t then matchs(S,s) else raise UNIFY

else matchs(S,(x,t)::s)

| matchs((t, V x) :: S, s) = raise UNIFY

| matchs((T(f,ts),T(g,us)) :: S, s) =

if f = g then matchs(zip(ts,us) @ S, s) else raise UNIFY;

(* match: term * term -> subst *)

fun match(pat,obj) = matchs([(pat,obj)],[]);

exception NORM;

(* rewrite: (term * term) list -> term -> term *)

fun rewrite [] t = raise NORM

| rewrite ((l,r)::R) t = lift(match(l,t)) r

handle UNIFY => rewrite R t;

(* norm: (term * term) list -> term -> term *)

fun norm R (V x) = V x

| norm R (T(f,ts)) =

let val u = T(f, map (norm R) ts)

in (norm R (rewrite R u)) handle NORM => u end;

alpha prolog or lambda prolog as a librtary would be good. alpha leantap (an interpreter)

import janus_swi as janus

# leantap with higher order unify?

# trs with higher order unify?

janus.consult("hounify", """

ho_unify(bvar()).

ho_unify(app(F1,X1), app(F2,X2)) :- ho_unify(F1,F2, Sig), ho_unify(X1,X2,Sig).

ho_unify(lam(X1,B1), lam(X2,B2), Sig) :- gensym(S), V =.. [S|Sig], X1 = V, X2 = V, ho_unify(B1,B2,Sig).

% noiminal_unify(T1, T2 , Perm)

nominal(atom(A), atom(B), Perm1, Perm2) :- member(A-B, Perm1), Perm1 = Perm2.

nominal(atom(A), atom(B), Perm1, Perm2) :- +/ member(A-Y, Perm1), +/ member(Z-B, Perm1), Perm2 = [A-B|Perm1].

nominal(app(F,Args), app(F1,Args2), Perm1, Perm2) :- nominal(F,F1)

nominal

% maybe a dcg of the permutation? We are threading a state.

nominal(atom(A), atom(B)) -->

% https://stackoverflow.com/questions/64638801/the-unification-algorithm-in-prolog#:~:text=unify(A%2CB)%3A%2D%20atomic,B)%2CA%3DB.

unify(A,B):-

atomic(A),atomic(B),A=B.

unify(A,B):-

var(A),A=B. % without occurs check

unify(A,B):-

nonvar(A),var(B),A=B. % without occurs check

unify(A,B):-

compound(A),compound(B),

A=..[F|ArgsA],B=..[F|ArgsB],

unify_args(ArgsA,ArgsB).

unify_args([A|TA],[B|TB]):-

unify(A,B),

unify_args(TA,TB).

unify_args([],[]).

""")

bottom up ho unify is simpler. Dowek. Maybe anmm inverse method/magic set is in order.